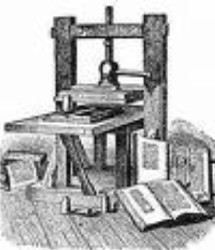

The defining moment that signalled the end of the Middle English period and the beginning of the Modern English period (1500-1800) was the introduction of the printing press in the second half of the 15th century. Its obvious direct impact was to make books more available to common people and thereby to improve their literacy. However, there were more subtle influences. Printed books led to pressures to standardize grammar and spelling. A reflection of this thrust was the publication of the first English dictionary in 1604. As in modern dictionaries, entries included guides to the pronunciation of the words. Thus, two significant movements were set into place. (1) With the adoption of fixed spelling and grammar rules, no longer would words be written with multiple phonetic versions. (2) The common people gradually adopted the pronunciation standards that were used in the dictionary, namely the pronunciation in London where the printing presses were located. The anglicization of Scotland had begun. London was a long way from Scotland. However the impact of anglicized standards was still felt - primarily through the one book that all good Scots read - The King James Bible. Naturally, pronunciation would not be transmitted as profoundly as via the written word, but certainly the English way of spelling became the standard for all of Great Britain. I suspect that this is the reason why we find the [ght] combination in our surname as opposed to the [cht] letters which better reflect the Scottish dialect.

Pronunciation standards were affected by a second major change which we refer to now as the Great Vowel Shift. This shift in how words were pronounced occurred gradually. It may have started during the Middle English period, but it became quite marked in the 1400s and 1500s. The rate of adoption varied greatly which explains why our surname might be spelled differently from parish to parish: they were pronouncing it differently. The net effect of the Great Vowel Shift was to change the pronunciation of the long vowels from a French sound to the long vowels we know now. For Wightons, one vowel change made a big difference in how our surname was pronounced. The Old English vowel [i] with its sound of {ee} as in {machine} became the [long i] sound in such words as bite.

During this period, certain spelling standards were adopted as a way to signal how words were to be pronounced. One such convention led to the second most common spelling of our surname, namely Weighton. The [ei] combination was used to signal that the vowel should be pronounced as a [long i] sound just as we would pronounce bite.

It was during this time that a second spelling convention - one which all of us use daily - was introduced: The silent e. Before this was introduced, the final [e] was always pronounced. Thus, the word WRITE would be pronounced as WREETA. The short vowel [I] was pronounced with the {ee} sound we're learned about and the final [E] was pronounced as in the final sound in China.) However, as the pronunciation of vowels changed through the Great Vowel Shift, the [E] at the end of a word became a signal that the preceding vowel was to be pronounced as if it were long. The [E] itself became silent. Thus, WREETA became WRITE. We had a few surname variants with a silent E, for example Wightone and Wightoune, but generally speaking, the silent E didn't affect us a lot.

A parallel convention did have a big impact though. It wasn't just the silent, terminating E that was used to indicate that a preceding vowel was to be pronounced as though it were long. Another such silent signal was the [gh] letter combination. As with the silent E, the silent GH meant that the preceding vowel was long and the [gh] should not be pronounced.

One final note: As everyone is aware, English is not spoken exactly the same throughout Great Britain. There are obvious regional dialects. One such dialectical difference is found in how the last part of our surname was pronounced. For example, in Scotland, the words Come down! might be pronounced more like Cum doon! Likewise, the last syllable of Wighton might be pronounced toon in Scotland but more like tun elsewhere.