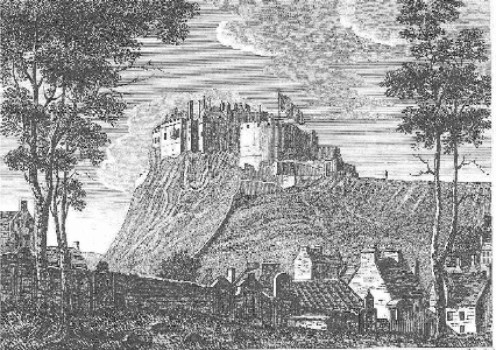

Built on an easily defended outcropping of volcanic rock, Edinburgh is located on the south bank of the Firth of Forth, approximately 40 miles south of Perth (as the duck flies and swims across two estuaries). Signs of human activity have been found dating back to at least 5000 BC. Two thousand years ago, during the Iron Age, Castle Rock on which Edinburgh Castle sits, had a hill-fort settlement on its summit. Early inhabitants include Celts, Romans, Northumbrians, and Scots. In about 600 AD, the stronghold, known as Din Eidyn (hill fort), was besieged and taken by the Angles. They called the place Eiden's Burgh and the name Edinburgh grew from that. (There's another theory: Edwin was the King of Northumbria who captured the fortress around 600. Edwin fortified the place and, in time, a town of huts surrounded the castle. Some claim that the city's name originated as Edwin's burgh. )

During the medieval years, Scottish rulers tended to base themselves further north (e.g., in Perth/Scone); however, King Malcom III built his castle at Edinburgh, his wife Queen Margaret built a chapel within its walls, and their son built the Abbey at Holyrood, a mile to the east along the Royal Mile. At the time, the Abbey was situated outside the city. The castle and abbey became Edinburgh's anchor points and a thriving town developed between them. The city was made Scotland's capital in the 15th century. In face of threats of sieges, Edinburgh was made into a walled city. (Over its history, Edinburgh had three sets of walls: The King's Wall, 1450-1475; the Flodden Wall, 1514-1560; and the Telfer Wall, 1626-1636.) With increased population, the walled city had no way of expanding outwards, so it had to grow upward. Houses inside the city's walls became multi-storey tenement buildings. The need for protection was real - Henry VIII sacked Edinburgh in the 1540s as part of his (subtle?) encouragement for Mary to marry his son. (Some men bring a ring; others bring armed forces.) During this period, Edinburgh became the country's largest trading center, due in part to its proximity to the busy port of Lieth whose main export was hides. The city itself became famous for its linen production. By 1550, Edinburgh's population had increased to about 15,000.

The 1600s started with the reign of James VI who became James I of England after Elizabeth's death. James spent most of his time in London and, as a result, Edinburgh's political power was greatly reduced. However, other institutions were established during this century, including the University of Edinburgh (above, left). Two outbreaks of the plague (1604, 1645) and occupation by the British (1650) slowed Edinburgh's growth for a time. However, later in the century, the Bank of Scotland (above right) was founded in Edinburgh and that was the start of the city's transformation into the financial center that it is today.

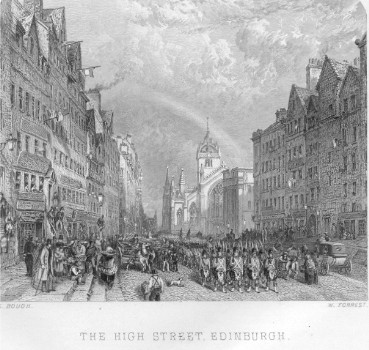

In 1707, when the Act of Union was promulgated, Edinburgh was a small capital city, consisting primarily of a single main street (High Street/Cannongate - above) running west to east from the defensive position of the Castle to Holyrood Palace. Narrow lanes (wynds) branching off on both sides gave it a layout like that of a fish skeleton. An overcrowded population of about 35,000, constrained within the city's walls, was crammed into multi-story tenement dwellings. Lack of proper drainage and generally unsanitary conditions created unhealthy conditions for its inhabitants. Visitors said that they could smell Edinburgh (a.k.a., Old Reekie) as they approached Dalkieth, 8 miles to the south. To the north, Leith prospered as a separate burgh devoted to trade, shipbuilding, and fishing. Leith, the entry point for luxury goods from Europe and beyond, was considered to be at the forefront of world shipbuilding.

After the Act of Union in 1707 and the transfer of government to London, Edinburgh's political importance essentially disappeared. Many of the prosperous governing classes moved south to London. The poorer elements of the population expanded, causing even further problems of overcrowding and disease in the tightly hemmed-in spaces of the medieval old town. Economic stagnation in Scotland as a whole following the union created an air of despondency and the Jacobite Rebellion followed in 1745. During this period of transition, Edinburgh became renowned as a center for writers, philosophers, scientists, and other intellectuals such as David Hume and Adam Smith.

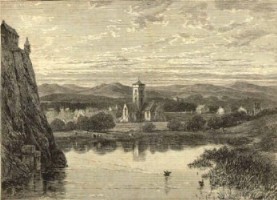

However, in time, the union with England brought increased prosperity into the city. Responding to its problems of overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and economic malaise, the city announced an architectural competition to design a New Town of Edinburgh north of the present city. Above left is the Nor Loch, the body of water separating Castle Rock (visible on the left) from the land north of the city. As shown in the picture on the right, the Nor Loch was drained and a bridge constructed linking New Town (not shown) to the old city (in the background). The old loch became the Princess Garden (below left).

Princes Garden, above left; a view of Edinburgh New Town (above right)

The project was intended to provide luxury housing which would attract absentee nobles back to Scotland. City fathers hoped that the wealthy would spend their money in Edinburgh and support the kinds of businesses and commerce that would bring prestige and prosperity to the city. The construction was completed in several stages from the 1760s to the 1830s and was an outstanding success in bringing commercial and cultural dynamism to the city. Edinburgh's economy flourished. For example, the demand for luxury products to furnish the new houses supported a range of fine shops on Princess Street. Carriage-makers prospered since the broad, straight streets were now able to support a more sophisticated wheeled traffic than was ever possible in the Old Town. All of these developments generated a significant surge in well-paid working class employment. There was a parallel demand for professional people, many of whom lived in the New Town. The financial sector grew rapidly as new banks were created to service the needs of the wealthy, the government, and increasingly the cotton, coal, and iron industries that were developing in western Scotland.

As the Industrial Revolution moved into the 1800s, Edinburgh continued to prosper by providing professional services. Banks gave financial support to Glasgow's engineering and ship building industries. Insurance companies were founded in response to the growing market for life insurance and firms of stock brokers and investment managers joined the city's professional ranks in the 1820s. Edinburgh became the most important financial city in Britain outside London. Stimulated by the city's professional needs (e.g., law, government, university), a massive printing and publishing industry was established. Some of the greatest publications of the period (e.g., the Encyclopaedia Britannica) were produced in Edinburgh. Brewing and distilling were also major industries. During the 18th century, Edinburgh enjoyed a remarkable reputation as a city of intellectual brilliance and beautiful architecture. Many new public buildings were built at great expense in the Greek neo-classical style, giving rise to its sometimes being called the Athens of the North. It was testimony to the prestige of Edinburgh that at the height of this golden age, in 1822, King George lV made his celebrated visit to the Scottish capital - the first British monarch to travel north to Scotland in over a century. (And this time, the king didn't bring an army.)

While the wealthy and professional inhabitants were enjoying newfound prosperity, the same could not be said for the poor. The Old Town tenements around the Royal Mile had declined into slums. In 1834, a destructive fire swept through the Old Town and destroyed 400 homes. The squalor of life for the poor in the overcrowded and disease-infested Old Town became increasingly marked. There were cholera outbreaks in the early 1830s (and again in 1848-49), and such infamous outrages as the Burke and Hare murders of the 1820s - committed in order to supply medical students with anatomy subjects.

By the 1900s, Glasgow had grown to become Scotland's largest, and most industrialized city. Edinburgh continued to prosper, but in a different way, relying on the professional industries of banking, insurance, and law. By 1917, the city had 317,000 inhabitants, an increase of more than 100,000 in just the previous 30 years. Printing, brewing, and distilling remained the principal industries of the city.

Sources

Various web sites, including

Edinburgh Town Guide (http://www.s-h-systems.co.uk/tourism/edinburgh/history.html)

The Rise of Edinburgh (http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/state/nations/scotland_edinburgh_01.shtml)

Further reading: Wighton Families in Edinburgh