The parish of Kirriemuir lies in north-western Angus on the northern side of the extensive and fertile valley of Strathmore. The southern part of Kirriemuir parish is reasonably flat and then it rises gently, forming almost one continuous sloping bank. This part of the parish lends itself to agriculture and manufacturing. The northern part of the parish (also referred to as Glenprosen) consists of the large valley along the Prosen, flanked by lofty mountains which rise on either side and which are intersected by numerous small glens and openings. As seen in the above two images, this part of the parish is chiefly pastoral and offers good pasture for cattle or sheep.

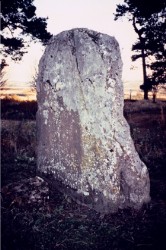

The village of Kirriemuir, Gateway to the Glens, lies in the southern part of the parish. The roots of Kirriemuir stretch back at least to the Bronze Age as suggested by the stannin stane (see right) - one of the town's well known features. There are now two pieces of what was one large stone - one part now lying on the ground. The standing part is 9 feet high above the surface of the ground and is 6.5 feet wide at its base. The resting part of the stone is almost 13 feet in length. The stone is believed to have been an ancient Pictish altar but, in truth, nothing is really known about it. Another 17 Pictish stones discovered in the area confirm that this was an important Pictish site.

Evidence of the Romans also has been found in the area. However, it was not until 1201 that the town's name was recorded in writing - in this case as Kerimor. Since then, there have been over 30 different spellings of the name. In 1459 Kirriemuir was made a Burgh of Barony which gave the town the right to have a weekly market, resident craftsmen, a market cross, and the right to buy and sell. Unlike Dundee (18 miles away) which had a Royal Charter, Kirriemuir could not engage in foreign trade, but it held a unique status in that it was the only Burgh of Barony in Angus.

For centuries, Kirriemuir served as the market town for neighboring parishes and that was what stimulated its growth. The land in the northern part of the parish was too steep, too high, and didn't have the soil to support much farming, but it could support herds of cattle and flocks of sheep. The southern section of the parish had better soil, but that soil became too spongy in wet weather to generate good crops. In 1795, the author of the Statistical Accounts observed that the landowners had been making numerous improvement to their properties, including draining wet areas, enclosing their lands, and using leases to force farmers to apply modern methods of crop rotation. Few if any leases are let in which the tenant is not bound to a regular rotation of cropping, and those who have old leases and are not bound, begin to find it their interest to follow one.

However, with its poor soil, Kirriemuir's future lay with its status as a trading market. No town in the country had a better weekly market; in none of its size is more trade carried on, according to the author of the Statistical Accounts in 1795. Substantial exports from the village included black cattle, sheep, poultry, butter, cheese, honey, wool, and tallow. Some local landowners had also begun to raise horses, and the most intelligent of the breeders of sheep have begun to raise lambs for sale to other sheep herders. Industry was also present. With three tanning yards in the village, about 1200 pairs of shoes were made annually for export. However, it was the manufacture of coarse linen that would become Kirriemuir's major industry. Two annual fairs were held in the village - July for sheep, horses and cattle; October for flax, wool, labouring utensils and household necessities.

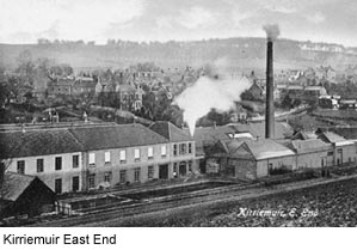

By 1833, Kirriemuir's growth in linen manufacturing was being fed by the migration of farmers forced off their lands by the practice of converting small farms into large ones. The village's population had increased from 4,421 in 1801 to 6,425 in 1831. The attraction to Kirriemuir was the prospects of jobs in the linen industry with at least 3,000 individuals employed. As noted by the author of the Statistical Accounts who wrote in 1833: Such is the ingenuity of our weavers and such their industry that we are not only able to compete with our rivals in the more favoured towns on the coast, but even to bear away from them the palm of victory. In proof of this, I have only to mention that upwards of 50,000 pieces of linen, of various fabrics and qualities, are annually manufactured among us; and that several mill spinners in Montrose and Dundee, towns possessing many natural advantages to which we can lay no claim, have been accustomed to send their yarns to be woven in this distant quarter - a measure which they never would have recourse to, did they not find it in their interest to do so.

The author of the accounts also sounded a warning of a recent trend. This manufacture, when flourishing, has certainly afforded a fair remuneration and support to those engaged in it, but for several years past, it has not done so to those who have pursued it on a small scale. The reason for that decline was the arrival of two textile factories and the era of handloom weaving in cottages would soon disappear.

Sources

Various web sites, including

Old Kirriemuir (http://www.angus.gov.uk/history/features/oldkirrie.htm)

Statistical Accounts of Scotland (http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/)

Further reading: Wighton Families in Kirriemuir