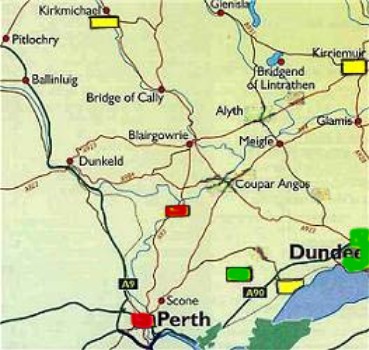

Kirkmichael Parish is in the shape of a parallelogram, approximately 17 miles long (north to south) and 6-7 miles broad (east to west). Although its southern border touches the northern border of Alyth Parish (in itself a large parish with the town of Alyth at its southern border), Kirkmichael is considered a Highland town. (The village is close to nearby Glenshee, home to Scotland's premier skiing center.) The image above left is a view looking west from Mount Blair towards Kirkmichael, the small collection of houses in the middle of the valley. In the map (above right), Kirkmichael is the yellow rectangle in the top left corner. You can see how far Kirkmichael is from the Wighton centers of Alyth and Coupar Angus in pre-Industrial Revolution Scotland.

Recorded history of the area tells of settlements having existed in the region as early as 200 BC. Although a particularly tranquil village, Kirkmichael has witnessed some major events in Scotland's history. Oliver Cromwell's troops were stationed in the village in 1653 (a battle taking place in the churchyard). It was here too that clans sympathetic to the Jacobite cause mustered in 1715 before marching south. The prevailing language in the parish in 1795 was Gaelic. To the right is a picture of the modern village of Kirkmichael.

Above - two views of the Strathardle Valley which contains much of Kirkmichael Parish.

Kirkmichael Parish's thin and dry soil generally yielded light crops. With the parish being in elevated and generally open and unsheltered land, the growing season was short. The climate was colder and more exposed to the severity of a cold or stormy season than surrounding parishes. Frosts were frequent through nine months of the year and could cause severe damage as they did in 1791 and 1792. Kirkmichael Parish's land was better adapted for pasturage than for tillage and tenants often relied on the sale of cattle to pay their rents (even though these rents were much less than in more fertile areas of Perthshire). Produce (e.g., potatoes, barley, oats) from the land was seldom sufficient to supply the inhabitants.

The suitability of the land for pasturage rather than farming meant that landowners could make more money raising sheep than potatoes. The author of the 1795 Statistical Accounts noted in that the population of the parish had been declining since 1755 due to the land being converted into sheep farms and the inhabitants being forced to migrate to other countries. Those that remained existed under the old conditions whereby tenants had to perform services for their landlords, such as helping in hay time, in harvesting, or in collecting fuel.

The Minister writing those 1795 accounts added some personal commentary to what was normally a dry accounting of a parish's life. The following are direct quotes from the Statistical Accounts which provide an interesting glimpse into what was happening at the time. Regarding the loss of population as a result of the conversion of farm land to sheep rearing, he said.

Is the increase of population in towns a full compensation for its diminution in the country? Is the strength and security of the State augmented? Is the acquisition of more numbers, and of wealth, an equivalent for the depravation of morals, and the decay of public spirit? Is the sum of happiness in the body of the people increased? Is a town life as favorable as a country life, to the culture of religious affections and of the social virtues? If the country should be depopulated, is it easy to replace its inhabitants? Or is it true that "A bold peasantry, their country's pride, when once destroyed, can never be supplied?"

He then described some of the challenges that parish farmers faced.

Few of the tenants enjoy leases of their farms. Holding their small possessions by a short and uncertain tenure, they are kept continually in a state of abject dependence on their landlords. It must be manifest to every observer that the situation in which the peasantry are thus retained has a strong tendency to repress the exertions of industry; to extinguish the ardour of patriotism, that attachment to his native soil, which glows spontaneously with such warmth in the breast of a Highlander. Is it that the landlords are apprehensive of deriving no benefit to themselves from granting leases; or of their tenants not having money or skill, or industry for making improvements? Or, is it that the tenants are unwilling to bind themselves for a number of years to modes of cultivation with which they are little acquainted? Or is it that men on whom wealth and power have conferred one kind of superiority find, in the exercise of that superiority, and in receiving that servile dependence of their inferiors, a gratification which they cannot be persuaded to relinquish?

While some ministers wrote only glowing accounts of their parishioners, this author was not reluctant to comment bluntly. Here's what he had to say about the town of Kirkmichael's weekly markets.

Weekly markets are held at Kirkmichael on Fridays whither the people of the neighbourhood repair, to sell what yarn they have spun during the week, and to buy their weekly supply of tobacco, snuff, lamp oil, and other groceries. It has been remarked, and perhaps with too much reason, that this market gives encouragement to idleness, and imprudent, not to say immoral indulgences, by furnishing a pretence for frequent visits to the village. Appointments for paying trifling debts are commonly made at this market. The creditor and debtor meet. They adjourn to the public house. After each has drunk his pot, the debtor finds he is not able to pay his debt. He craves a week's delay. The creditor easily agrees to so short a term. The appointment is renewed and the same scene repeated, perhaps many times, before the debt is paid. Thus both time and money are needlessly spent, and a habit of idleness and of tipling contracted.

Finally, here's an interesting comment about a trait of the village's inhabitants that would prove to be a source of great wealth and success when the entire village of Kirkmichael migrated en masse to the USA, registered in Yale Law School, and then dispersed across the country.

The greatest fault in their general character is that they are too much disposed to litigation, for which they are noted by their neighbours. Three sheriff-officers and a constable residing within the parish find abundance of employment.

Sources

Various web sites, including

Statistical Accounts of Scotland (http://stat-acc-scot.edina.ac.uk/)

Further reading: Wighton Families in Kirkmichael