King David I (1124 to 1153) started Scotland's economic growth in the middle ages by stimulating the growth of Scotland's most important burghs by granting them a Royal Charter. Such towns had an exclusive right to buy and sell goods in foreign markets. The focus on trade enabled Dundee (and other Royal Burghs) to attract foreign goods and trades people that Scotland lacked at the time. These goods and people came from Flanders, northern France, Scandinavia, and of course England. Their common language was English and it was the importance of Scottish burghs that caused the English language to spread throughout the country. Exports from early Dundee were primarily raw wool, sheepskin, hides and fish. Dundee's principal trading partners were in the Low Countries (modern Belgium and Holland), France and the Baltic.

International trade flourished (and with it Dundee and Scotland's prosperity) only when relations with England were peaceful. If not, trading between England and Scotland would be diminished and, as well, English hostility would deter other traders from dealing with Scotland. Even though trading ships sailed in convoys for protection against English pirates, Scottish seaborne traffic was affected. And, of course, Dundee's prosperity was directly affected by any military action against it, as described previously. For example, Dundee was badly damaged during the religious wars which culminated in 1/6 of its population being killed by the British in 1651. The city was still recovering from this devastation when Scotland joined with England in 1707. The Act of Union had an initial depressing effect on Dundee's economy. The principal export at the time was coarse woolen fabric called plaiding which was exported to Holland where it was treated and dyed and then sold as army uniforms in Germany. Dundee lost its right to trade with Holland and France as part of the Act of Union and so this entire business was devastated. Nor surprisingly, the city's populace favoured the Jacobite side in the uprising of 1715. However, over time, that sentiment changed as Dundee began to benefit economically from the union. Trade in various forms of linens became the primary export and Dundee had regained much of its prosperity in 1745 when the Jacobite cause was put to rest at Culloden by Cumberland. The city offered the Duke Freedom of the Burgh and the approximate 12,000 inhabitants of Dundee entered a period of growing prosperity.

By 1790, the 24,000 strong city of Dundee had a thriving linen export business that included coarse fabrics, ship canvas, bagging for cotton wool, coloured thread, tanned leather, and cordage of all kinds for shipping and ropes. Although most of these products were manufactured right in Dundee, the surrounding parishes provided up to 1/4 of the linen products and spinning labour. Spurred by the Industrial Revolution, the town itself began to see rapid growth. The city expanded rapidly with empty land being used to develop housing. Within the city proper, there were new buildings and churches, paved streets and gas lamps. New piers were built and the harbour generally improved for the 100+ ships belonging to the port.

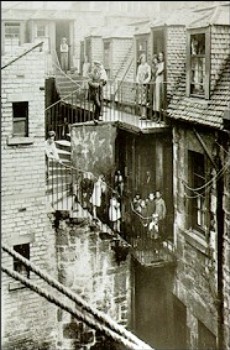

Reverend Small, the author of the Statistical Account of Dundee in the 1790s, did raise some concerns about the impact of the rapid growth. The first was for the relative health of the inhabitants. Though the linen manufacture be the great source of their opulence and increase, its influence does not seem so favourable as might be wished to health, or friendly to the production of a vigorous and hardy race. He also commented on the living conditions in the city - the narrow lanes, the buildings crowded so close to another, the high number of people living together under one roof, the building of additional suburbs without any general plan and without the least regard to health, and the lack of educational institutions. Unfortunately, his concerns would prove to be well-founded as shown in the two pictures above.

In the early decades of the 19th century, Dundee received samples of a new fibre from India. It was called jute and it made Dundee into a boom town. Dundee had an ample work force of women who were adept at spinning and weaving coarse linen into products that could be made by jute, the nearby whaling industry supplied ample oil to make jute easier to weave, the port gave Dundee excellent trading connections, the local shipbuilding industry was able to build the big, fast boats able to transport jute from India, and growth in world trade lead to an increased demand for sacking and baling materials that were made from jute. At the same time, the industrial revolution provided mills and plants that could take advantage of this new demand.

Dundee's population exploded from 26,000 in 1801, to 40,000 in 1835, to 90,000 in 1861, and to 130,000 by 1871. Some of the new citizens were Irish immigrants escaping the potato famine. The rest were Scots moving off the land and into the city. Most were employed within the jute industry. Cox's Stack (picture to the right), a 282 ft. tall brick chimney to the Cox Brother's mill, became a landmark in the city and the centerpiece of what was to become the largest jute works in the world. (This Cox family also purchased the Potento estate in Meigle where the earliest ancestors of the Meigle line of Wightons had worked back in the 1700s.) This single mill employed 3,200 people and had 17 steam engines driving 560 looms with over 10,000 spindles. At its height, 50,000 people were employed in the jute industry.

Mill workers had to endure hard working conditions including a large number of people crowded into confined locations, heat, dust, fumes and noise - all of which made workers prone to respiratory problems ("Mill Fever") and deafness. In 1845, the hours of work were from 5:30 in the morning to 7:00 in the evening with half an hour off for breakfast and another half hour off for dinner. As the author of the Statistical Accounts related, people of all ages were employed. "Old men and old women no longer able to undergo the labour of the loom, and young persons of both sexes not yet strong enough for that work, are employed in winding for the warper and the weaver, and thereby contribute something to the general funds of the family. More than half of the people employed in 1845 were boys and girls between the ages of 10 and 18.

Meanwhile, housing and sanitation struggled to accommodate the booming numbers. Workers mostly lived in overcrowded, one- or two-room tenements close to the mill or factory at which they worked. Families slept in box beds, often four to a bed. If sanitation existed at all, it was a communal WC in the stair tower of the tenement. Extremely poor sanitation led to cholera and typhus epidemics that swept the city in the late 19th century.

The jute industry began to decline when Indian mills entered the market with lower prices. This had a significant effect on Dundee which struggled to compete but couldn't. Dundee did have other industries such as jam (marmalade was invented in Dundee) and journalism to help it to survive. The city suffered badly during the depression of the 1930s but regained life during the war when its shipbuilding industry operated non-stop. The city now has diversified light industry, including a strong tourism sector.

Sources

Various web sites, especially

Reverend Small, Statistical Account of Dundee in the 1790s, Statistical Accounts of Scotland, http://edina.ac.uk/stat-acc-scot/

Towns and Trading in Scotland (http://netmedia.co.uk/history/week-18/)

The Union of the Scottish and English Parliaments (http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/lennich/1707.htm)

Verdant Works, a jute mill museum in Dundee (http://www.rrsdiscovery.com/verdantworks/archive/index.html)

Further reading: Wighton Families in Dundee: Part 2