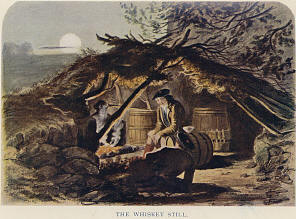

Above, a depiction of an illicit whiskey still

From the first attempts to make whisky until the 19th century, distilling was largely a Scottish cottage industry, closely tied to the cycle of the seasons. The Highlander would sow his hardy barley seeds in spring, harvest his crop in late summer and dry the grain throughout the winter. The discarded straw was used for his animals and to insulate his cottage floor. By March, when ice had disappeared from the streams, distilling began.

A small copper pot still often stood in the corner of the cottage, heated by a fire of glowing peat blocks. The fermenting mixture of home-grown barley and stream water was heated and the vapour passed down a tube immersed in water. Distillation in crude pot stills was something like simmering beer in the kettle and cooling the vapour. The raw, condensed spirit was not matured but decanted into jugs and small casks for immediate use. Whisky was a communal, convivial spirit, believed to have medicinal properties, and often exchanged with clan neighbours for rent, goods or services rendered. It became a cornerstone of community life. At one time it was used for barter, almost as a form of currency. In the 16th century, for instance, a farm in Kintyre paid six quarts of whisky as rent.

The Scots Parliament first imposed an excise duty on alcoholic beverages in 1644. But, since it was very difficult to collect, it was generally ignored. Cromwell, during his control of the country, reduced the rate but proved more efficient in collecting it.

In 1707, after the Scots and English parliaments amalgamated, the excise duty was harshly stepped up to try to price whisky out of the reach of the working class. Further taxes were levied in 1725. Instead of taxing whiskey directly, the tax was levied on malt at the rate of 3 pence per bushel. As this would have netted the government minimal revenue, it is generally accepted that Prime Minister Walpole was thinking more in terms of asserting English authority in Scotland. Indignant Scots responded by going on the rampage in Glasgow and maltsters flatly refused to allow excisemen to check their stocks. English revenue officers poured across the border in a determined effort to collect the tax.

The long term effects of the tax were considerable. Because it was also a tax on ale (the favoured beverage of the common man), it put up the price or lowered the quality of the product. In time, the popularity of ale diminished and whiskey replaced it as the main drink of the people. Parish Ministers in the Statistical accounts bemoaned the loss of ale as the most popular drink, arguing that ale had nutritional value whereas whiskey had none. A more likely negative difference between the two was that whiskey was much stronger. There was a second consequence as well. The duty sparked widespread anger in Scotland. Within months, almost the entire country - highland and lowland - turned to smuggling.

In the large, licensed distilleries of the Lowlands, the distillers increasingly used unmalted grain together with the malted barley to minimise the effects of the tax. It certainly did not improve the quality of the whisky and contributed to the demand for the product from the Highlands which was of better quality though most of it had probably paid no duty at all. Much of the product of the distilleries in the Lowlands was exported to England to be re-distilled and rectified to form gin.

Among the Lowland peasantry, male and female alike engaged in illicit distilling, there being no more persistent devotees than some of the goodwives who had got into the habit of rinnin' a dram, and getting it quietly marketed as they best could. Many depended for payment of their rents upon what they could make by this means, and landlords had obvious reasons to wink at the smuggling which prevailed with their knowledge to such an extent among their tenants. The following is a quote from a Col. Thornton, a magistrate, on an event that occurred while he was traveling.

As I passed, we saw a tribe of gentry, whom I took to be smugglers, and being in good spirits, I gave them to understand some custom-house officers were behind in search of them. They thanked me for my hint, and availed themselves of it by leaving the road instantly, which confirmed my suspicions, and I thought they unloaded their goods on the moors, but the day turning foggy and we soon lost sight of them.

There was nothing disreputable in the practice in the public opinion of their neighbourhoods and nothing disgraceful in being caught by the Excisemen, or gaugers as they were called. Such a mishap might, indeed, be inconvenient; but then the awards of the Justices were not of formidable severity. They would at times sit a whole day adjudicating cases of private malting or distillation, and, in the course of the entire sitting, impose no higher penalty than half-a-crown or so upon any one of the dozen or score of delinquents arraigned before them.

At a highlander's bothy

In the 18th century, Scots drank huge quantities of whisky, far more than anyone today would appreciate. Some hosts had the stems struck from wine glasses to ensure continuous drinking and round-bottomed bottles, which had to be passed from hand to hand, were in continuous use. Toasting was a popular after-dinner entertainment, and in Perthshire a rule applied that if any guest failed to empty his glass to a toast, he had to drink the same toast a second time from a full glass. Whisky, easily made from local grain and water, remained cheap in rural areas where duty was often ignored.

Distilling became an act of patriotism and Scots saw no good reason for paying for the privilege of making their own national drink. Illicit whisky distilling, like the secret wearing of the tartan, became an act of rebellion. To Highlanders, whisky-making represented a way of life as important as the right to gather fuel, grow grain or keep cattle. Distilling came to be regarded as an heroic act of proud defiance against the English. The busiest highways in Scotland were whisky roads over the hills, used by smugglers hauling barley or malt to hidden stills, or lined with ponies carrying kegs of spirit. On some whisky trails convoys of up to 150 pack-horses carried bulk supplies to the cities in the south.

Nearly every highlands farmer had his own stilI, In the vastness of the Highland districts it was difficult to discover the bothies, where the work was carried on, and prudence often forbade the gauger from attempting a seizure. But in more accessible parts of the country, his keen search could only be evaded by the utmost vigilance. In some localities where a mutual bond of protection existed, it was the practice, when the exciseman was seen approaching, to display immediately from the house-top, or a conspicuous eminence, a white sheet, which being seen by the people of the next town, or farm steading, a similar signal is hoisted, and thus the alarm passes rapidly up the glen, and before the officer can reach the transgressors of the law, everything has been carefully removed and so well concealed, that even when positive information has been given, it frequently happens that no trace of the work can be found.

The outlaw life turned out to have unforeseen advantages for the illicit distillers. Fleeing deeper into the hills to avoid the exciseman led to the discovery of water sources of great purity, in addition to ample supplies of peat and barley. Meanwhile, bureaucratic regulations governing the size of stills and strength of washes badly affected the quality of whisky at licensed Highland distilleries. They found it difficult to compete with a hand-crafted product lovingly produced in secret by men who slept alongside their stills.

In spite of the government's attempts to control the production of whiskey, illicit stills and smuggling abounded. In 1777, there were 408 stills in Edinburgh alone and only eight of them paying duty. By this time, whisky was so popular as a national symbol that the middle and upper classes were even drinking it for breakfast. In 1782, about 1,940 stills were seized with little effect on whisky production. By the early 1800s, whisky was fast becoming the most important industry in Scotland. Half the quantity sold was made illegally, often by skilled distillers who had been bankrupted by excise duty.

The government responded by raising the taxes. In 1786, the production of whiskey was taxed at the rate of 30 pound per gallon. The rate increased year by year until in 1802 it had risen to 162 pounds per gallon. The final heights of absurdity were reached in 1814 when the Government prohibited all stills within the Highland line of under 500 gallons capacity. This was in effect a complete interdict on the legal distilling of whisky in the Highlands. The result inevitably was that even more illicit spirit was produced.

Aware that trying to collect whisky duty was draining its resources, the government concluded that the only way to curb illicit distilling was to encourage whisky-making under controlled conditions. The government finally capitulated and introduced a reasonable licence fee for distilling in 1823. The Act enabled distillers to operate without fear of prosecution by paying a licence fee on all stills with a capacity of 40 gallons or over. Skilled craftsmen welcomed the opportunity to work without risking imprisonment. Many who came in from the cold selected the same sites and water sources to keep up the high standards of their smuggling days. Smuggling died out almost completely over the next ten years and, in fact, a great many of the present day distilleries stand on sites used by smugglers of old.

The Statistical Accounts of the 1790s talk about the impact of whiskey on Scottish life at the time. By far the greatest number of adverse comments made by parish ministers, where such were given, concern the immoderate drinking of whisky. In account after account, the writers attack what they clearly see as the outstanding social evil of the day; many too bewail the loss of the greatly preferable home-brewed ale which whisky had universally replaced after the Malt Tax was introduced in 1725.

Many of the complaints were targeted on the tippling houses which, in the view of the writers, were far too numerous. Here are a few comments:

Such places ensnare the innocent, become the haunts of the idle and dissipated, and ruin annually the health and morals of thousands of mankind.

The effects of public houses, are most injurious to the morals and industry of the people, especially when little else than whiskey is sold in them. A few pence procures as much of this base spirit as is sufficient to make any man mad.

The number of dram houses is out of all bounds too great. These haunts of the idle, the prodigal and profane, contaminate the morals of the lower classes of the people beyond description. A poor widow must pay a tax, before she can obtain a candle to give her light, in spinning for the support of her fatherless children; and yet a dram-seller can get a license for little more than one shilling to corrupt the morals of the lieges for a whole year.

Sources

Steven, Maisie (1995). Parish Life in 18th Century Scotland: A review of the old Statistical Accounts Glasgow: Scottish Cultural Press

Various web sites, including

Electric.scotland.com http://www.electricscotland.com/history/home/chapter18.htm

Perthshire Diary: www.perthshirediary.com

Rural Life in the 18th Century (www.electricscotland.com/history/rural_life17.htm)

The Scotch: http://www.suntory.co.jp/whisky/Ballantine/chp-03-e.html