Above, the Allan Shipping Line's S.S. Pretorian as presented on a vintage postcard

The Pretorian was built for the Allan Line in 1900 in West Hartlepool (North-East England) by Furness, Withy and Company. The ship was about 437 feet long and 53 feet at its beam and had one funnel, two masts, a single screw and a speed of 13 knots. Initially designed for 50 first class passengers, 150 second class passengers and 400 third class passengers, she was rebuilt in 1908 to accommodate 200 second class passengers and 900 third class passengers. Harry and family sailed on her in 1915 as third class passengers. The ship had been sailing on the Glasgow to Quebec/Montreal schedule since 1904. In 1917, she became part of the Canadian Pacific Ocean Services and was taken out of service in 1922. Below is a series of information sketches of life aboard a steam ship in the early 20th century.

Life on board an ocean Liner for 3rd class passengers (1904)

Steerage is by no means as bad as it sounds, although, on the other hand, it is not all beer and skittles. The steerage conditions of thirty or forty years ago, when they herded you below decks like cattle into one common room, minus privacy, ventilation, bedding and eating utensils, no longer prevail. Today, the third class passengers on the big liners travel in comparative luxury. There are regular staterooms accommodating from two to six persons, and special ones for families. A dining-room, with crockery dishes, good food and stewards to do the serving, form an agreeable contrast to the old days when a man had to furnish his own tin cup and plate, and then rustle for himself at meal times, the food, generally insufficient and poorly cooked, being served in huge pots, from which the strongest grabbed the most. There is also, on the modern boats, a smoking room, a general lounging-room and plenty of washing facilities. It is really not half bad, especially at the price. (Source: GG Archives, Crossing the Atlantic like a Seasoned Ocean Voyager)

Here's a description of what third class would be like on the Scandinavian line in 1917.

The third class staterooms — all of which are spacious, and well ventilated — are comfortably furnished with iron beds, springs, mattresses, sheets, pillows and woolen blankets, wash-stands, mirrors, towels, soap and water. Supplied with fresh drinking water. Kept in order by stewards and stewardesses. They accommodate two, four and six passengers, this arrangement enabling whole families to keep together. Meals are served by uniformed waiters in clean dining rooms at tables set with clean linen and porcelain tableware; and the food is of good quality cooked in the palatable Scandinavian style, and served plentifully and with wide variety in the menus. Ample deck space for open air promenading and exercise is reserved for the third class passengers. Ladies' saloon, well furnished; comfortable smoking rooms; barber shops and many baths are a few of the conveniences furnished to those traveling in this class. The services of physician and nurse, and the facilities of a well-equipped hospital and dispensary are at the service of passengers. The same standards of courtesy and cleanliness that make travelling in the first and second cabins of this line such a delight will be found in this class, too. Women and children travelling alone are in the care of a special matron and stewardesses.

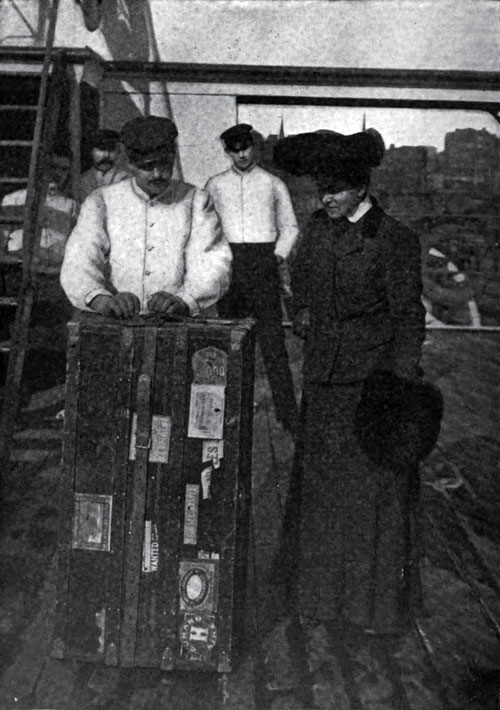

Stewards on an ocean liner (1909)

Stewards slept in the bowels of the ship, where there might be five or six good-sized rooms, all filled full of tiers of bunks where the sleepers laid side by side. The stewards' boxes were stowed under the tiers. There was no other furniture. Like all other rooms in the ship, the stewards' sleeping quarters were inspected daily and so the linen on the thirty-inch-wide bunks was good and clean, and the bunk rooms were scrupulously neat. An incandescent light burned day and night, and fresh air was piped into the room through long pipes leading from the ventilators on deck.

To retain his position as steward on one of the big liners a man had to be wise, tactful, and energetic. But, honesty was the first requirement. To their credit, even though passengers might leave money and jewels exposed in their staterooms, a steward rarely was tempted. Once he had been even suspected, his days of usefulness were over, and he left the ship at the first dock.

A steward's pay was not large. Typically, the steward received fifteen dollars a month (or 3 pounds), in addition to his food and lodging, while at sea. He might make twelve trips a year making his annual wages less than 200 dollars. Out of this sum, he had to buy his own uniforms and pay his own laundry bills. Moreover, he had to pay fifty cents a trip to the "boots" who kept his share of the sleeping cabin clean, fifty cents in each port to the shore steward who served his meals while the ship was at the dock, and fifty cents each round trip to have his storage box taken away from the ship and returned if he was re-hired for the next voyage. (Stewards were automatically discharged at the end of each voyage.) In one article, I read that stewards were also automatically charged one shilling and nine pence ($0.43) for breakage whether there had been any breakage or not. Given this low salary, to make a living, the steward had to receive tips from the passengers that he served.

For saloon stewards, their day started at five-thirty in the morning when they were mustered in the dining saloon, ate their coffee and rolls, and got to work. They were on duty in one way or another till eleven at night. After all the passengers had breakfasted, they ate their own breakfast at about ten while standing informally in the pantry. Lunch was served to the passengers at about three and dinner was at eight. Between meals, there were the tables to be laid, and cleared, and relaid, the silver to be cleaned, the saloon to be swept and put in order, and a host of minor things to be attended to.

Deck stewards were continually on their feet during the same hours, serving tea or bouillon between meals, and attending to those passengers who were sitting on the decks in steamer chairs. The bedroom stewards had similar long hours, for example in cleaning and caring for the cabins under their responsibility. In addition, each took a watch from eight to twelve p.m., twelve to four a.m. or four to eight a.m. - ready to answer calls from the various staterooms.

For some stewards, while promotion up the ladder to chief steward might be attractive, for others, the plum job was the smoke-room steward. It might have less dignity and importance than the chief steward. And, it certainly was demanding. The smoke-room steward had to be deft, tactful, vigilant, and untiring. He had to be on his feet from dawn to midnight. But the smoke room was where the millionaires on the boat spent their time, and their tips. (Source: mostly GG Archives: Stewards on an Ocean Liner.)

Life on board an ocean liner for the engine room crew (1909)

Above, a steward letting the engine crew know that the captain wanted to water ski.

In the engine room, the stokers and coal-passers and trimmers work four hours on and eight hours off. The stokers receive $22.50 and the pursers and trimmers $20.00 per month. I was unable to see their sleeping quarters; but their labor representative in Liverpool told me that their "bunkrooms" were anything but models for light and ventilation; that the narrow compartments in which these men sleep are at fully Turkish bath heat temperature. I saw the place where they eat. It is a small, narrow compartment, and may be likened to a damp, hot stable. Benches and tables are of the rudest possible construction. Those I saw at a meal had bread, tea, and a sort of stew. The Baltic has sixty of these men. The thirty-six sailors work four hours on and four off; they are paid $20 per month. Their bunks are ranged round the forecastle, and they were sleeping in their clothes when I saw them; the discolored mattresses and blankets looked ready for the rag-shop or the disinfecting chamber.

On contemplating the lot of the sailors, stokers, and coal-handlers of a steamship, one asks himself how it is that men can be found who will consent to get down to such dreary, painful, and ill-requited toil, performed under such hard conditions. As a fact, every man to whom escape is possible must flee from that sort of life. It must be the more helpless characters, from whatever cause, who remain. One thing is to be remembered; the men are bound to work the round trip from England; for if they quit at New York, they forfeit the pay already earned. And another, at Liverpool 22,000 dock laborers report at the gates alongshore every day seeking a job; and on the average only 15,000 find employment. The "surplus" 7,000 indicate the possible state of unemployment of maritime labor in Great Britain. (Source GG Archives, but note that a different author wrote this article than the author who wrote about the stewards and their clean living quarters.)

Provisioning the Deutschland, a trans-Atlantic liner (1901)

Above, a ship's bakery

The Deutschland had sixteen boilers in the boiler-room which consumed 572 tons of coal per day which, for a 5-7 day voyage meant 2,800 or 4,000 tons of coal. However, the ship's total coal capacity was about 5,000 tons and bunkers were pretty much filled at the end of each voyage.

For a ship carrying 1,100 passengers, there would be a crew of 550. Seventeen hundred souls would constitute the inhabitants of many an American community. To feed these people for a period of six days required, in meat alone, the equivalent of fourteen steers, ten calves, twenty-nine sheep, twenty-six lambs, nine hogs and some 1,500 chickens, geese and game. The ship's larder was also stocked with 1,700 pounds of fish, 400 pounds of tongues, sweetbreads, etc., 1,700 dozen eggs, 14 barrels of oysters and clams, 1,000 bricks of ice cream, 1,300 pounds of table butter, 2,200 quarts of milk, and 300 quarts of cream.

In the way of vegetables, ship larders contained 175 barrels of potatoes, 75 barrels of assorted vegetables, 20 crates of tomatoes and table celery, 200 dozen lettuce and 4 tons of assorted fresh fruits. The daily supply of bread, biscuits, cakes, etc. required 90 barrels of flour, each weighing 195 pounds. This item alone added 8.5 tons to the cooks' stores. To this, add 350 pounds of yeast and 600 pounds of oatmeal. Under the heading of liquids the most important item was the 400 tons of drinking water, 12,000 quarts of wine and liquors, 15,000 quarts of beer in kegs, besides 3,000 bottles of beer. Last, but not by any means least, was the supply of 40 tons of ice. (Source GG Archives)

Sources

Gjenvick-Gjonvik Archives: http://www.gjenvick.com

The Pretorian: Ancestry.com: http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/TheShipsList/1997-10/0876749343