Scottish women working in a munitions factory.

"Touch me like that again, and I'm going to put your hand in this vise and ..."

| Glasgow's Munitions Industry |

|

|

| Scottish women working in a munitions factory. |

"Touch me like that again, and I'm going to put your hand in this vise and ..." |

|

Glasgow creates a new industry In mid-May, 1915, public outrage over a shortage of shells on the western front toppled the Liberal government and led to the formation of a coalition government. British soldiers were wounded and dying because they didn't have enough armaments and the new government took immediate action to address this. The economic and industrial future of the British Empire was dependent on whether the government could quickly create a vast munitions industry. That industry could only proceed with the co-operation of all skilled workers - meaning there could be no more labour unrest from the increasingly strident trade union movement. It would also depend on whether the industry could make do with unskilled labour to replace the former skilled workers who were now in the army. The imposition of conscription in January 1916 meant the unskilled labour for the British munitions industry had to be made up primarily by women. A Ministry of Munitions was created in June, 1915 under the control of Lloyd George and in the next few years, he would oversee the creation of a massive new industry that churned out millions of tons of artillery and shells that would supply not only the British soldiers, but also those of the Allied Forces. Glasgow was the industrial heartland of Scotland and its Clydeside industrial region became one of the most important centres of munitions production in Britain. The shipyards, iron foundries and steel works were rapidly converted to munitions production. The Glasgow area was ideally suited for the new industry because it contained large supplies of coal, iron and steel, a concentration of experienced engineering firms, and a skilled male workforce. It also had a large reserve of female labour. For the rest of the war, women in the west of Scotland would make all manner of materiel crucial to the war effort including aeroplanes, tanks, howitzers, sea mines, cartridges, fuses and shells of all sizes. They participated in all the processes of shell making, from forging the steel in the foundry to polishing and packing the finished product, and they performed a broad spectrum of work, ranging from highly skilled tasks to heavy manual labour. Throughout the course of the war, as the munitions industry expanded and as the army conscripted more men, women increasingly took on more strenuous work and performed more skilled processes. The creation of this new industry was not without its problems. Clydeside industry before the war had overwhelmingly employed male labour and it had become such a hotbed of the new trade union movement that it was known as Red Clydeside. The unions considered the conscription of skilled workers and the use of unskilled workers, including women, to do the work of skilled workmen as dilution and vigorously opposed it. They were mollified, somewhat, by the government's agreement that the skilled workmen would be guaranteed their jobs when they returned from the war, although labour unrest did continue. It was this environment that Harry and his family entered in August, 2015. By January, 2016, he was looking for work. He found it in the munitions industry. Working conditions in munitions factories |

|

|

|

There was no shortage of women willing and anxious to get into munitions work. Eventually tens of thousands of Scottish women worked in Clydeside during the Great War to the point where upper and middle class women loudly lamented the loss of their domestic servants to munitions work, and textile manufacturers complained bitterly about the depletion of their workforce to the new munitions factories. Munitions work was closely identified with patriotism and doing their bit for the war effort. However, the primary attraction for the majority of women was undoubtedly the opportunity it afforded them to earn very high wages. Those high wages would come at a cost. The urgency to equip the fighting forces meant that the government had to balance the need for munitions against the need for workers to rest. Urgency for munitions won that particular battle. Although the Factory Law of 1901 had restrictions on how many hours women and children could work, exemptions to this law were granted automatically to any munitions factory that asked. Overtime on munitions work became virtually universal and, as well, women and children were employed in night work and Sunday work. Many factories operated 7 days a week, 24 hours a day either in 3 shifts of 8 hours each or 2 shifts of 12 hours each. Workers were doing sixty, eighty, and even one hundred hours a week. For example, at one factory, women would work 11.5 hours from 6:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Sundays to Fridays with two hours off for meals during the day. On Saturday, they worked only six hours from 6:00 a.m. to noon with 3/4 of an hour off. Night shifts lasted 12.5 hours, from 5:30 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. But, those hours were just what women spent in the factory. They also had to get from home to factory and back again. Depending on the distance between their home and the factory, and the availability of public transport, many would face a long, dreary walk in darkness and often in cold, wet weather. On arriving at the factory, the women had to work for two to three hours before stopping for breakfast. Add to this as well, the long queues they had to endure to get food at the canteen, the difficulty in working in ill-ventilated and poorly-lit workshops, the extremes of temperature that they were exposed to, and the hardships of carrying out dirty, heavy, and potentially dangerous manual labour. The hardships and difficulties of munitions factories were so great that most women could not tolerate the work for any length of time. Typically, only 10% of a factory's work force remained on the job for twelve months. High wages came at a high price in terms of the deterioration in the women's health. Excessively long hours of heavy manual labour often performed at a very fast pace contributed not only to widespread fatigue but also to a high incidence of industrial accidents among munitions women. Labour unrest in the industry 1915-1919 |

|

|

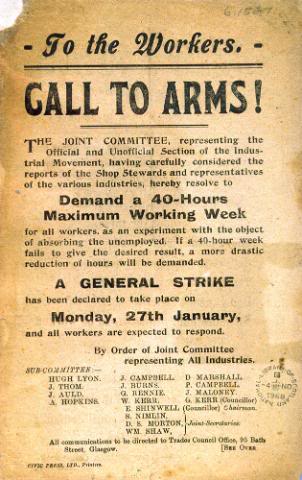

| A poster calling for a general strike on Monday, January 27, 1919. |

The "bolshevist uprising" in Glasgow's George Square, January 31, 1919 |

|

The largest munitions factories were built, equipped, and operated entirely with public money. In return for funding contracts, armament firms managed the plant, agreed to provide a quantity of shells of a certain calibre within a specified time, and charged the Ministry a negotiated price for the finished products. Their fee for services was based on a percentage of the cost of construction, as well as a commission for each shell produced. When the amount of government money pouring into the industry became apparent, many medium and small companies clamoured for contracts and were employed as sub-contractors to the large firms. Non-engineering firms joined in the rush to convert themselves to munitions work. From 1916, new factories were constantly being erected and seemingly every place that could hold a lathe was in the munitions business. Nor surprisingly, with factory owners receiving a commission for each shell produced, the work environment was ripe for abuse. Employers encouraged women to accelerate their work by paying them through a piecework system. While this could be beneficial to the workers as they could earn more and more money, piecework was also detrimental to the health of women workers as it caused them to overexert themselves, often to a dangerous level. Employers were fully aware of the effect of piecework on unsophisticated workers and some prodded the women to work even harder by paying them bonuses for producing the highest number of shells per shift, for example. This could lead to injurious over-exertion in the last hour of a shift. Keep in mind that many women were the sole provider for their families as army wages were notoriously irregular. This exploitation came at a time of intense social and industrial unrest that was already rampant in the area. Even before the war, the trade union movement was taking hold. But, with the war, Glasgow, Paisley, Greenock and Clydebank became a hotbed of socialist ideas and protest. Marxist activists organized demonstrations to protest against the capitalist war and the local socialist newspaper kept up a weekly barrage of criticism against the government's handling of the war. In April 1915, irate at wartime rent increases and profiteering landlords, housewives in Glasgow tenements organized rent strikes that received widespread support. Ultimately, thirty thousand households refused to pay rent. The solidarity of the working class women was so strong that it could not be broken by the rent collectors, who then had to apply to the courts to evict the tenants. But, whenever sheriffs tried to enforce an eviction notice, hundreds of people turned out to bar their entrance into the neighbourhood. In the face of such massive working class solidarity and action, the landlords changed their tactics in October 1915, and attempted to pursue tenants thought the small claims court. That month 18 munitions workers were summoned to the court for non-payment. On the day of the hearing, 10,000 protesters from all over the city made their way to the court house to demand that the charges be dropped and that the rents be frozen at their original levels. If this was not done, a general strike would be called for 22nd November. The government was terrified by the rising working class radicalisation, and gave in to the demands of the strikers. The Rent Restriction Act followed, which fixed rents at their pre-war level for the duration of the conflict all over the UK. Government leaders backed down on the rent strikes, perhaps because the protestors were mostly women and they were peaceful, albeit persistent and effective. But, they had an entirely different reaction when 10,000 engineering workers from munitions factories in Glasgow led a wildcat strike for higher wages. The Munitions of War Act, proclaimed in July 1915, made strikes a criminal offense. The act also empowered the Minister of Munitions to enforce the admission of unskilled labour into the munitions workplace - the dilution effect that the workers bitterly opposed. However, the part of the statute that infuriated the workers the most was the law that prevented a munitions worker from leaving his current place of employment and assuming a similar job in another factory unless he received permission from his current employer to do so, something that factory owners were not going to do. Without that permission, the worker would have to remain unemployed for six weeks before taking up that new job. Workers argued that this law bound them to one employer in a form of slavery that cost them their personal freedom. Agitations continued into spring of 1916 as the organization representing the workers insisted that dilution was acceptable only if it was done under the workers' control. The bosses refused to negotiate. In retaliation, workers at one large plant struck. Workers at other munitions works also struck in sympathy. Heightening tensions and the spread of revolutionary rhetoric culminated in the deportation or imprisonment of shop steward leaders and socialist agitators in March, 1916 (just as Harry was preparing himself to enter the industry). With the Clyde's hard core of troublemakers removed, dilution proceeded apace as thousands of women entered engineering workshops and shell factories. A form of labour peace continued to the end of the war. However, although they had no choice but to tolerate women during the war, when the war ended, the unions demanded that the government remove the women from the work site so that the men could have their jobs back. The government fulfilled its wartime pledges to the trade unions by passing the 1918 Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act. 100,000 women in the munitions workforce were suddenly out of work with only two weeks wages in lieu of notice. In Scotland, post war employment prospects for women were extremely bleak. Local newspapers encouraged former women munitions workers to return to their prewar employment in textiles, laundry, dressmaking, and service. But some women who applied for reinstatement in their pre-war places of employment received harsh treatment and frequently outright rejection. Some firms simply refused point blank to reinstate former workers. A fortunate few were finally offered employment but at considerably reduced wages that, in some cases, were less than their cost of lodgings. Under some duress, the government finally took some steps to set up training programs for post war employment, but they trained them in the age-old, low paying, unskilled work of domestic service. When women resisted the return to the bondage of domestic service, they were accused of being too choosy and preferring to live off of government doles while good jobs lay vacant. Glasgow newspapers had applauded women munitions workers during the war, marvelling at their skill, cheerfulness, unfailing patriotism and impressively high output. But, in the post-war years they treated them with indifference and even hostility, referring to them as the 'idle rich' and railing against their refusal to take service work. Women munitions workers, who had been indispensable during the war, became objects of public animosity in the immediate post war years. Tensions reached a peak in 1919 when Glasgow workers began a drive to get a 54 hour work week reduced to 40 hours. High unemployment had followed the end of the war and the unions wanted to distribute what work remained in the city to more of its members. When negotiations failed, the union led a general strike that began on Monday, January 27 1919 and continued for a week. A mass meeting was called for Friday, Jan. 31 in George Square. With upwards of 60,000 people in the square, the assembly turned violent with workers and police engaging in pitched battles. The government called it a bolshevist uprising and sent in the troops late Friday night and early Saturday. Worried that Glasgow-based troops could not be trusted, soldiers from outside of Glasgow were used. The Battle of George Square, also known as Bloody Friday, ended with ten thousand troops armed with machine guns, tanks, and a howitzer occupying Glasgow streets. An estimated 100,000 English troops were sent to Glasgow in the immediate aftermath. The strike was called off on February 19th when the striking workers achieved a 47-hour work week. Harry's job as a shell inspector |

|

|

Above, two shell casings that Harry brought home to Canada (smuggled in the soles of his shoes to avoid detection) |

|

Since many munitions contractors and subcontractors had no experience in the field, defective munitions were bound to be common. Problems included shells not detonating, fuses falling out in flight or just not working, shells varying in size, casings too big, etc. Making munitions requires precision and not all contractors could do that reliably. This meant that quality control was a serious need for this new industry and the government was forced to send its own inspectors into the factories to sort out the problems. Where did these inspectors come from? It's quite likely that men who had enlisted to fight in the war but were unable to serve would be considered for that post. That's probably how Harry got the job. But, women predominated among Scotland's government inspectorate, constituting 88% of its 1,500 strong workforce at the beginning of 1917. (Baillie) The shell inspection process went like this. After shells were completely machined, they then went to the varnish room where women attached the shells to hoists and then dipped them into vats of varnish. From there, they went to drying stoves for two hours. The final destination was to a bonding store, a secure facility outside of the shell factory that was designated as government property. It was here that government inspectors would examine the shells. If approved, the shells' casing would be painted by women using a pistol like appliance served by one pipe of paint and another pipe of compressed air. When dry, the shells were then transported to another site to be filled with explosives. From Baillie we also learn that government inspectors were not appreciated very much. Government inspectors conducted the final scrupulous examination, their fastidiousness and frequent rejection of work causing bitter resentment among workers and management alike. It's understandable that shell inspectors would be disliked. Every shell rejected was a commission not earned. Of course, there's also the other side of the story. Every shell rejected could be a Scottish soldier's death that was averted. Before you started this description of the munitions industry, I had posed the question: Why did Harry's income vary so widely?. We now have the probable answer. Pay in the munitions industry was based on piecemeal work. Contractors got paid for each shell they manufactured. Workers got paid for each item they produced. It's entirely likely that shell inspectors were also paid on a commission system and possibly they too were able to (compelled to?) work overtime. That would explain why, in some months he'd be earning over $140 Cad - a princely sum. Sources The Women of Red Clydeside: Women Munitions Workers in the West of Scotland during the First World War (2002). A Ph.D. Dissertation by Myra Baillie. http://digitalcommons.mcmaster.ca (Or google the title for a pdf file.) Various websites, including Munitions Factories: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/scotlandshistory/20thand21stcenturies/worldwarone/munitionsfactories/index.asp Red Clydeside and the shop stewards' movement. http://libcom.org/history/articles/red-clydeside Battle of George Square: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_George_Square Bloody Friday: http://urbanglasgow.co.uk/archive/-bloody-friday-glasgow-s-general-strike-of-1919.__o_t__t_792.html Great War Forum: Discussion on defective shells: http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=124300 A National Projectile Factory. An article in The Engineer, July 28, 1916. http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/images/7/7f/Er19160728.pdf The Glasgow rent strike: http://libcom.org/history/1915-the-glasgow-rent-strike |