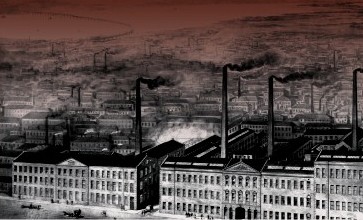

Mechanization of Dundee's linen industry had very far-reaching social consequences. The new machines were expensive, and beyond the pocket of most of the spinners and weavers who had kept cloth-making going as a home-based cottage industry. Also, the machines were bulky, and really required special premises. For these reasons the industries passed into the hands of specialist owners, who could buy the machines and build sheds in which to install them, thereafter paying workers to come and operate them. These manufactories had to be built near the source of power - running water to begin with, and then near coal-fields when steam-power came to be used. The workers had to follow the work, and the owners of the machines and factories began to provide housing near the workplace for the convenience of the workers. So it came about that the old independent handloom weavers, and domestic spinners, working to commissions or contracts in their own homes, were superseded by two very different groups - the owners of machines and premises who controlled production, and the paid employees who carried it out. Thus emerged the new classes of decision-making owners, living off the profits of their industries, and wage-earning workers, operating to instructions and under supervision. Obviously the interests of these groups would clash, especially as workers sought to maximise wages and owners sought to maximise profits.

Jute is one of the most versatile natural fibres known to man. Raw jute fibre is obtained from two varieties of plant: Corchorus Capsularis and Corchorus Olitorius, both native to Bengal (modern day Bangladesh). (Calcutta, now Kolkata, is located in Bangladesh.)

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, jute was indispensable. Its uses included: sacking, ropes, boot linings, aprons, carpets, tents, roofing felts, satchels, linoleum backing, tarpaulins, sand bags, meat wrappers, sailcloth, scrims, tapestries, oven cloths, horse covers, cattle bedding, electric cable, even parachutes. Jute’s appeal lay in its strength, low cost, durability and versatility.

Weaving, whaling and shipbuilding were the three vital ingredients that made Dundee the jute capital of the then modern world. Weaving was an important occupation in Dundee as far back as the 16th century, so the skills were already in place to adapt to jute processing. The local whaling fleet provided the whale oil needed to soften the jute and make it workable. And Dundee’s ship building industry (another offshoot of the whaling heritage) was put to work to construct the big, fast ships that brought the jute from India. On top of which, new worldwide markets were opening up for jute products, a fact the enterprising merchant community was quick to recognise.

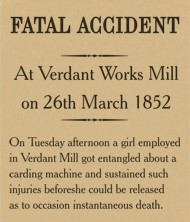

Work in the Dundee jute mills of the 19th century offered little but drudgery, exhaustion, low wages and constant danger. Most of the workers were women and children (they cost less to employ) and employment law was virtually non-existent. And there was always the risk of accidents with the machines, graphic descriptions of which were common reading in the local newspaper.

In this day and age it’s hard to imagine the working conditions. Everybody would be covered in dust or stour, clogging eyes, mouths and noses. The noise of the machinery created an ever-present, ear-splitting din, with the result that many workers went deaf. Women outnumbered men three to one in the mills, an imbalance in the labour market that gained Dundee the nickname of she town. It created a unique and tough breed of women, born out of being the main providers for the family. The mill girls were noted for their stubborn independence. Overdressed, loud, bold-eyed girls according to one observer and often roarin’ fou’ with drink – characteristics that caused consternation among the gentlefolk of Dundee.

Working alongside the women would be thousands of children. Again they commanded only low wages, and being so small meant they could pack the machines closer together. Children under nine would work as pickers, cleaning dust from beneath the machines.

Health hazards were unavoidable. The heat, dust, grease and oil fumes caused a condition known as Mill Fever, which would lead to respiratory diseases like bronchitis.

This poem was written by Mary Brooksbank, a former Dundee jute mill worker. The poem is titled Sidlaw Breezes but it also might be appropriately named Jute Mill Song.

Oh, dear me, the mill's gaen fast,

The puir wee shifters canna get a rest.

Shiftin' bobbins, coorse and fine,

They fairly mak' ye work for your ten and nine.

Oh, dear me, I wish the day was done,

Rinnin' up and doon the Pass is no' nae fun;

Shiftin', piecin', spinnin' warp weft and twine,

Tae feed and cled my bairnie affen ten and nine.

Oh, dear me, the warld's ill divided,

Them that work the hardest are aye wi' least provided,

But I maun bide contented, dark days or fine,

There's no much pleasure living affen ten and nine.

Sources

Various websites, including:

Scotland: A concise history. (http://www.electricscotland.com/history/scotland/chap9.htm)

Dundee Heritage Trust: (http://www.rrsdiscovery.com/index.php?pageID=63)

Scots Independent (http://www.scotsindependent.org/features/singasang/dearme.htm)