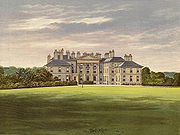

Above: An 18th century Scottish residence.

While some Scots lived in palaces like this in the mid-18th century, the gudeman's house was typically a simple, single storey linear building with at best two habitable rooms (the but and the ben) and a garret, with the byre and stable under the same roof. They all looked much alike; low in the walls and thatched with straw interlaid with thin turf sods to bind the roof, and overlooking the great dunghill in which all manner of excrement, humans as well as animal, was kept in readiness for the annual manuring of the bearland. The dwelling house itself was perhaps 30' long and 14' wide.

The BUT contained the kitchen, dining room, and the sleeping quarters for the maidservants and the gudeman's daughters. (The men and the grown sons of the tenant slept in a loft above the BEN if there was one, or more commonly, with the animals in the stable.) The floor of the BUT was earthen, the walls were unplastered, and there was, as a rule, no ceiling below the rafters although there might be a few planks nailed between the beams to serve as shelves for storing food. The only window was a foot and a half wide, and a little higher, filled with lozenge glass. The main feature of the room was the enormous 'lum' or chimney built over the cradle grate and projecting five or six feet into the room. (When wind conditions blew the smoke into the house, the maidservants and daughters might have to sleep in the byre or stable.)

Benches were arranged comfortably around the fireplace where the boys and menservants would sit in the evening together with any hangers-on the family might acquire. Apart from the benches there would be a great table bearing earthenware plates and tankards as well as spoons, also a number of cupboards or chests, spinning wheels and other household implements. The BUT was a crowded, warm, smoky, busy place where everyone connected with the farm was equally welcome and where discipline and order were kept by the gudewife.

The BEN was the private apartment of the gudeman. It had an earthen floor, plastered walls, a recessed fire, and possibly a wooden ceiling. In other respects, it was similar in appearance and dimensions to the BUT. The gudeman and his wife slept in the BEN along with their younger children. Furniture in the BEN might include chairs and a small table, an easy chair for the gudewife at barintime, and the best box bed. Sometimes there would be a writing desk and a chest for papers. Always there would be somewhere to keep the bible and other books belonging to the family.

In comparison, a cottar's house could be built in a single day if the materials had been gathered beforehand. It was a stone-walled hut, with walls about five foot high and 12 feet long on each side, an earthen floor, and a thatched roof. Not all had chimneys - in many cottages the smoke still rose from the hearth towards a hole left in the roof, or found its way out through the door or the unglazed window. The main piece of furniture in such a hovel was the box-bed, fully enclosed on all sides and accessible only by a sliding door in the front. Otherwise, there might be a couple of chests, two stools, a cooking pot, a wash tub, some wooden mugs, and horn spoons.

By the 1790s, there were numerous parishes reporting in the Statistical Accounts that housing conditions had improved significantly. Farm houses were built more solidly, with better roofs (e.g., slate), and with more than one storey. Instead of mean, dirty hovels built with stones without cement, houses were being built by good masons with mortar, cast on the outside with lime, and neatly finished within.

However, there were still many parishes where housing consisted of dirty, shabby huts. For example, in Clunie, Perthshire, the minister reported. The materials for building good houses abound in the parish; many of the people live in miserable smoky cribs, more like sties for hogs than habitations for men. Several of the farmers have too short leases, and some of them no leases at all. Consequently, they are discouraged from carrying on improvements to any extent.

It seems probable that where land owners were encouraging new farming practices (for example through better leases), the farmer's life improved with more produce, more income, and better living conditions. With William's occupation as a corn dealer, it seems reasonable to assume that he, Margaret, and their children, were benefiting from improved housing conditions as well.

Sources

Steven, Maisie C. Parish Life in Eighteenth-Century Scotland, Scottish Cultural Press.

Smout, T.C. (1998). A History of the Scottish People, Fontana Press.