You've probably read the essay on the cholera epidemics in 19th century Scotland that was part of the biography of John Wighton. But, cholera wasn’t the only infectious disease that Scots of this period faced. The most common causes of death in 19th century Scotland were:

- Diseases of the brain and nervous system;

- Diseases of the respiratory system;

- Diseases of the heart;

- Diseases of the digestive organs; and,

- Epidemic and contagious diseases.

Clearly, with epidemic diseases of all kinds ranked at #5 in the list, 19th century Scots faced some serious health issues. The diseases causing the most deaths were tuberculosis, typhus, scarletina, whooping cough, smallpox and measles. In the 1860s two-fifths of all deaths in Glasgow were due to respiratory diseases and tuberculosis. Respiratory diseases in Dundee were also widespread – as the John Wighton family experienced first hand with death to two family members from whooping cough and pulmonary congestion.

Epidemics and poor health were not simply the products of bad housing and defective drinking supplies. Part of the problem lay with conditions in the workplace. A study of Tranent, near Edinburgh, in the 1840s found that out of 35 colliers' families, the average age at death for the male head-of-household was 34, while the average age at death for male factory workers was over 51. That's not to say factories were a healthy, safe place to work. They certainly weren't - they just were better than coal mines (image to the left) with the diseases brought on by coal dust inhalation. Lung diseases were widespread across the whole of the working class. The risk of pneumonia and bronchitis was particularly high in the wet-spinning flax factories. The risk of tuberculosis and industrial silicosis was greatly increased by dusty work in the scotching and carding rooms, and the heat and closed atmosphere of some sorts of cotton spinning. Workers' resistance to disease was lowered even further by exhaustion. Employees were required to work between 12 - 13.5 hours. When you add in the time they were given for meals at work (half an hour to an hour for breakfast and perhaps a longer amount for a dinner), they could be spending 16 hours a day at work. Many workers preferred to continue work at meal times and leave early. A six day week was worked although Saturday was usually shortened so that workers could buy provisions. In the course of a year, there would be two holidays other than Sundays. Malnutrition also played a big role in lowered resistance to disease.

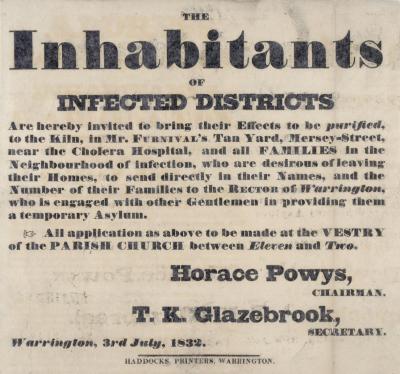

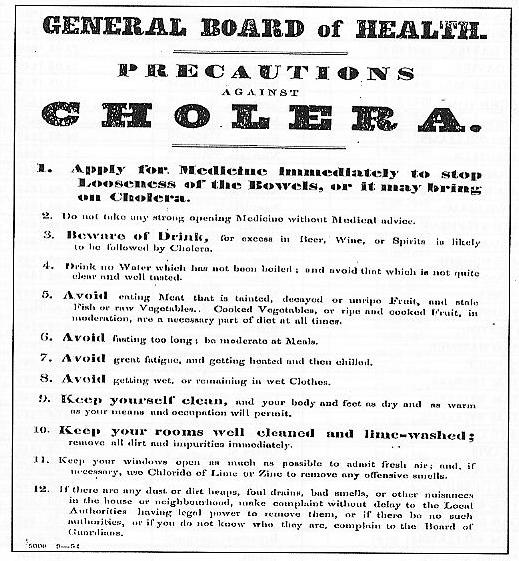

Ignorance of the basic principles of hygiene was also an important factor in the generation and spread of disease. Boiling water was not a common practice in the 19th century, nor was bathing popular. Dirty water and unclean bodies were major factors in the spread of diseases such as cholera and typhoid. Milk and other dairy products were a common breeding ground for scarlet fever and diphtheria. Dairies and shopkeepers diluted milk with (infected) water to yield greater profits. Of course, alcohol consumption, mainly of whisky, induced all manner of health problems, and Scotland's reputation for drunkenness was legend. The problem of food and drink pollution was addressed with a law in 1860 banning the adulteration of milk.

Much of the reduction in disease and other health problems that took place in the second half of the century was due to rising standards of living and changes in lifestyle. However, it was also due to improved public health administration and the provision of health care. Until the late 19th century most health care was provided by parishes and the standards varied according to the wealth of the parish. The whole system was haphazard and any improvements were down to local initiatives. It took until 1889 with the passing of the Local Government Act for public health affairs to be put on a more organised footing. The legislation required local authorities to appoint a medical officer of health, whose activities, and those of sanitary inspectors, were subject to the control and supervision of the Local Government Board. The appointment of medical officers of health meant that a whole host of environmental issues, such as air and water pollution, could be addressed and remedied. Encouragement was also given to the building of drainage and sewage systems in larger villages and small towns. Inadequacies in providing sanitary appliances in housing such as sinks and WCs were also dealt with. Despite the clear progress made in these areas by 1900 a number of outstanding issues still had to be addressed. Ash-pits and middens were still being used for human waste, and the removal of dirt and refuse was only being carried out once a fortnight, or less, in the large burghs. Moreover, the supply of water to homes was obstructed by ratepayers on grounds of cost. This led to the storing of water in the home, a practice which led to contamination.

Although progress was clearly evident in improving the environment and the water and sanitation systems, the slow pace of reform was small comfort to those stricken by disease and ill-health. Unless one was designated a pauper, all health care at this time had to be paid for privately. If a person was ill, there were three types of care available: treatment in a voluntary hospital; treatment in a poor law hospital; and treatment at home by a doctor.

The voluntary or teaching hospitals were superior medical institutions with first class facilities and staff. They were supported by private donations, endowments and subscriptions. To receive treatment a patient had to be provided with a 'line' signed by a subscriber. All patients had to leave the hospital within 40 days, and funeral expenses were to be guaranteed by the subscriber. Certain categories of patient were not admitted - the poor, (since poorhouses dealt with them), apprentices and servants, (who were to be looked after in their masters' houses).

From 1845, the very poor and those suffering from incurable diseases were treated in Poor Law hospitals. Managers of the hospitals were under pressure to keep expenditure down, something which led to economies in the provision of medical facilities. From the 1850s to 1870s operations for the removal of tumours were performed in the patient's own bed or on a table in the ward as there were no funds for separate operating rooms. At the busiest times of the year, patients, usually children, had to share beds. Baths, sinks and WCs were in short supply. In the Barony parish of Glasgow in 1883 the occupants of wards 141 (skin diseases) and 142 (venereal disease) shared the same WC and bath. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the problems in Poor Law hospitals were addressed. But it remained a fact that only those applying for poor relief could gain admittance to the system, the rest had to rely on the expensive voluntary hospitals or charity.

Those on poor relief could also receive visits from the parish doctor and call at his surgery free of charge. However, this outdoor medical service was stretched to the limit. The doctor was only employed on a part-time basis and the number of patients in his care was quite phenomenal. In the city parish of Glasgow in 1875 one doctor was employed for every 20,000 of the population. A doctor might have as many as 3,000 home visits in a year and yet this was supposedly on a part-time basis! Nevertheless, during the second half of the 19th century, the problems of ill-health and disease were being confronted in a serious manner by an assortment of means. Tuberculosis still remained one the most important causes of death, but infectious diseases no longer posed the threat they had earlier in the century. Typhus, scarlet fever and smallpox had all been nearly eradicated by 1901. However, it was obvious that, by 1900, despite these improvements, most Scots were receiving a standard of health care which was, at best, uneven in quality and, at worse, non-existent. (Note: Fanny Wighton, generation 6, died of influenza in 1884; Ella Burns Wighton, generation 7, died of TB in 1908.)

Sources

Various websites, including:

A Chronology of State Medicine, Public Health, Welfare and Related Services in Britain 1066-1999: http://www.fphm.org.uk/resources/AtoZ/r_chronology_of_state_medicine.pdf

A History of the Scottish People: Health in Scotland 1840-1940: http://www.scran.ac.uk/scotland/pdf/SP2_3Health.pdf

Urban growth in Victorian Scotland: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/victorian/features_victorian_urban.shtml