Scottish rural families in the 18th century enjoyed a healthier life than their urban counterparts, at least in one respect. The crowded conditions and the extremely poor sanitation made cities breeding grounds for all sorts of diseases. (People threw the contents of their chamber pots out the window and onto the street; the more sophisticated built privies hanging over the streets that jutted away from the sides so that excrement would not foul the walls.) Centuries earlier, these diseases had been known as the plague or the pest, but they might have been a number of diseases: bubonic plague as spread by flea on the black rat; typhus as carried by lice; typhoid fever conveyed in polluted drinking water; or the recurrent summer diarrhoea which was the fly-borne slayer of countless babies. Some of these epidemics were confined to the city itself; others were spread throughout the countryside by travelers (or marauding armies as was the case in 1644-48).

A general lack of attention to hygiene was also prevalent and contributed to the spread of a disease. For example, once a person recovered, it was common for the bedclothes in which s/he had lain ill to remain unwashed and to be used by other family members. Also, Scottish custom was for neighbours to think it their duty, or a piece of civility, to frequent the house of those taken ill, offering assistance and comfort and basically catching whatever disease the person had.

Records reveal the Black Death or an equivalent epidemic sweeping through Scotland in 1349/60, the 1430s, 1450, 1475, 1499/1500, 1545/46, 1568, 1575, 1584-88, 1598-1608, 1624, and 1644-48. In this last incident, an estimated 9,000 people were killed in Edinburgh; In Aberdeen, 1,760 people died out of a population of 8,000; and in Brechin, one third of the people died. After this last outbreak, widespread epidemics disappeared, although high urban death rates continued, particularly among children. People were used to this, accepted it as one of the hazards of town life, and did not attempt to change it until towns became much larger, more dangerous, and more crowded in the 18th and 19th centuries.

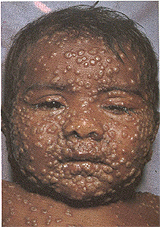

In the 1700s, the big killer was smallpox (see picture at top of the page). By 1760, smallpox epidemics were so common that it was estimated that only 2,000 of some 50,000 people hadn't been exposed to the disease. Of the remaining 48,000, 18% would die. At its worst, smallpox's death rate was 33%. It afflicted small children most seriously; for them, it was often fatal claiming 1 child for every 3 or 4 infected. Between 1783 and 1800, 19% of all of Scotland's deaths were due to smallpox. More than a third of the deaths of children under 10 were due to smallpox.

A smallpox vaccine was devised by Jenner in 1796 in England and adopted quickly by Scottish doctors. This vaccination gave the child an attack of harmless cowpox but conveyed immunity to smallpox. Some parishes accepted inoculation, others did not in spite of some appalling mortality to the disease. Even though inoculation was almost invariably successful, and even though most church ministers were advocates and some even set an example with their own children, many Scots retained a strong prejudice against it and refused to consider any evidence of its benefits because they believed that it usurped the prerogative of God. Gradually that attitude changed, pocket of resistance by pocket of resistance. By 1825 the disease had dropped from about 20% of all deaths to less than 2%.

As smallpox came under control, other diseases became more noticeable. Measles, for example accounted for 10% of all fatalities in Glasgow in the early 1800s. Diphtheria or croup was also prevalent. The minister in Deer, Aberdeenshire, for example wrote in 1790: No disease has of late years raged here with greater mortality than the putrid sore throat. It chiefly attacked children, sometimes, cutting off 1, 2 and 4 of a family. Another scourge was tuberculosis or consumption. It was estimated that one fifth of the deaths in the 18th century were due to this disease - mostly youths in their teens and twenties. (Stephen)

Exposure to dampness and rains contributed to a prevalence of rheumatism and fevers. As has been noted elsewhere, most members of a farming family wore no shoes, at least in the first part of the century. Also, most people lived in cold, damp houses with inadequate fuel to keep them warm. Staying in wet clothes after working outside also contributed.

Some parish ministers listed scurvy as a major problem in their contributions to the Statistical Accounts, as in this example. The scurvy is the most predominant disease; and is attended with violent symptoms, such as aching pains in the joints and limbs, and hard livid swellings; in some cases tumors are formed, which suppurate and degenerate into scrophulous runnings; in some instances it affects the judgement, and makes the unhappy sufferers put an end to their own existence. In another report in the Statistical Accounts, one author ascribed the cause of scurvy to idle indolent habits, unwholesome food, impure air, the want of attention to cleanliness, and a sedentary life. Another author blamed the frequent consumption of oatmeal. Fruit was practically unknown in some areas of Scotland and it wasn't until the early 1800s before the British Navy began issuing lime juice to its sailors. (Stephen)

In spite of the ubiquitous presence of fatal diseases, it's important to note that minister after minister in the Statistical Accounts described their parishioners as remarkably healthy or of a remarkably sound constitution, for example. It appears that the Scots who had survived the perils of an altogether hostile environment were, on the whole, quite remarkably fit and healthy, apart from the prevailing maladies, almost invariably cited as the rheumatism and sundry fevers. Moreover, many accounts told of a significant number of inhabitants who were not only long-lived, but healthy and still working a full day in their old age. From these accounts it is clear that the old in the community played a very active part.

The picture of a hardy people can be applied not only to the older age-groups but to the people as a whole. Writings of various 'tourists' of the time profess astonishment at the feats of endurance of which the Scots people were capable. Those comments were usually made in reference to the extremely frugal diet on which they lived. That diet - mainly dairy products, cereals and potatoes, with a few vegetables, lentils and eggs, a variable amount of fish but hardly any meat - may have been decidedly monotonous, but its high nutritional rating is clear.

Sources

Houston, R. A. and Knox, W. W. J. (2001). The New Penguin History of Scotland, London: Penguin Books.

Smout, T.C. (1998). A History of the Scottish People, Fontana Press.

Steven, Maisie C. Parish Life in Eighteenth-Century Scotland, Scottish Cultural Press.