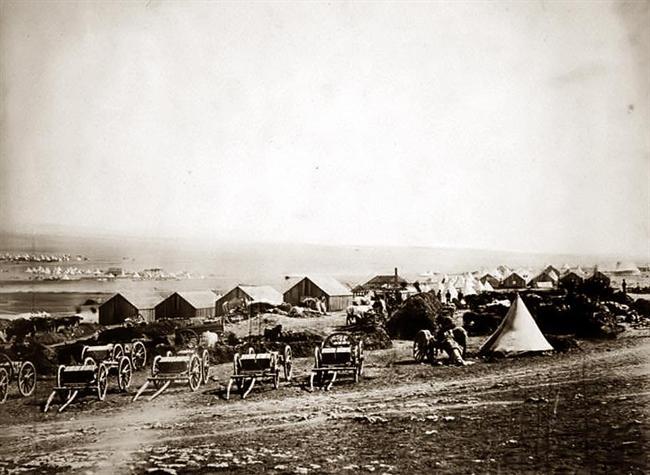

Above, the siege of Sevastopol.

The Crimea War, and within that the siege of Sevastopol, was part of the conflict between Russia and Turkey, a struggle for domination that came down from the preceding centuries. In the eighteenth century the Turks proved quite able to hold their own against all the power of Russia and they entered the nineteenth century with their ancient dominion largely intact. But they were declining in strength while Russia was growing, and long before 1900 the empire of the Sultan would have become overpowered by Czar Nicholas had not the other Powers of Europe come to the rescue.

Of the various wars which Russia waged against Turkey, the first of modern historical importance was that of 1854-55, known as the Crimean War and made notable by the fact that Britain, France and Sardinia joined the Turks in their struggle against the Russian armies. The Western powers had long been fearful of letting Constantinople fall into the hands of Russia. They had interfered to prevent this after the victory of Russia in 1829. War broke out again in 1853 and Russia seemed likely to triumph. This led Britain and France to declare war in 1854. They sent armies to the Black Sea, and in September 1854, a strong force was landed on the coast of the Crimean peninsula.

Their goal was the capture of the fortress of Sevastopol and the destruction of the Russian fleet in its harbor. But the Russian defense was vigorous and the stronghold proved difficult to take. Battles took place on the banks of the Alma and at Balaclava, in both of which the allies were successful, the latter being made notable by the heroic (albeit incompetent) British Charge of the Light Brigade.

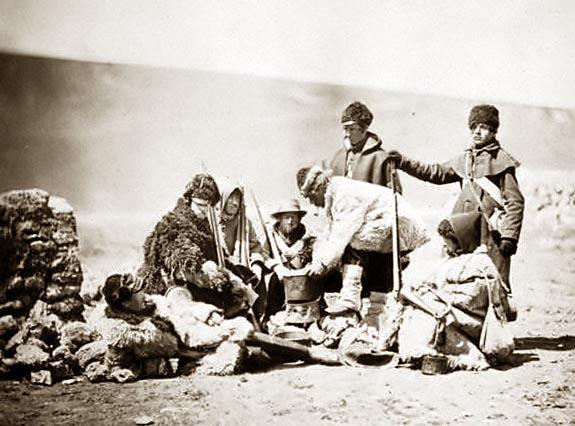

Above, artillery wagons.

Leadership mistakes were not the only problem facing the allied forces. Although they won the battles of Alma and Balaclava, the British and French armies were facing significant problems. The following is an extract from a soldier's (Charles Usherwood) diary at the time.

About this time of the month of October, the cholera began again to take off many men and in one tent alone I saw 6 to 8 men rolling over one another in the agonies of death they having been carried to this tent to die. Dysentery and diarrhoea too the old scourge of our army held fast to the various camps emaciating their victims and ultimately laying the cold hand of death upon very many of them. How to stop the ravages of these additional enemies the Medical Officers could not tell for the arrangements in the medical department were woefully deplorable and disgraceful in the extreme. Literally I have seen poor wretches turned away from the hospital covered as they were with filth and rags, to take care of themselves with perhaps only a Dover's powder washed down their throats by muddy water as an antidote for the acutest dysentery. One poor creature with a miserable form crawling as he was on all fours actually was refused either medicine or admission into hospital simply because they had none - there being only one hospital tent then available and which was unsupplied either with bedding, medical comforts, cooking apparatus and even sufficient attendance. Finding all appeal of no avail, the poor wretch made his way to the latrine and died near to the ditch of accumulated filth.

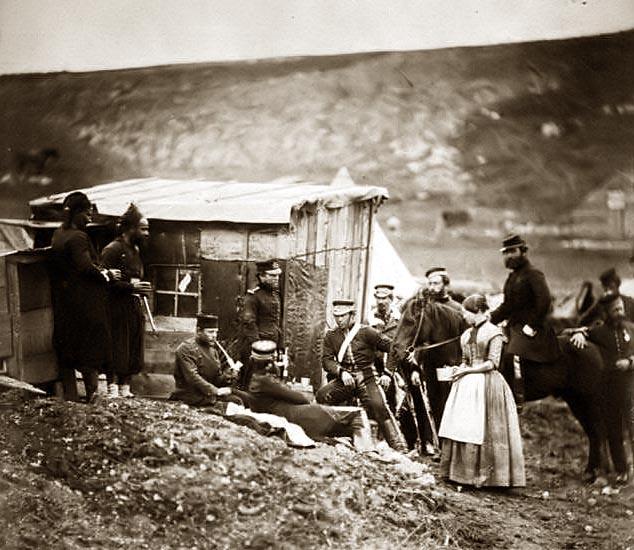

Above, troops in winter dress.

In the Fall of 1854, a British council of war met to decide whether Sevastopol should be assaulted or whether the army should withdraw from Crimea altogether. They finally decided to provide winter quarters on the heights above Sevastopol and await reinforcements. Had they been properly provided for, the army would have taken winter in its stride. Instead administrative chaos and confusion riddled the army, terrible storms lashed the camps and British ships suffered catastrophic losses in the storm of November 14th when Balaclava harbor masters denied entry to the ships. Tents were shredded and tree were uprooted. Equipment was ruined and the troops were freezing under the open sky. In Balaclava, there was no lack of food, clothing or stores. The problem was in moving the stores to the heights. This task proved beyond the capabilities of the Commissariat because there was not enough forage to feed the pack animals. The cavalry horses were also starved of forage and were eating each other's tails and manes. (Note: John was not present during this period.)

In December of 1854, the London Times was moved to attack the administrative chaos and muddle in the Crimea. The world began to learn how Florence Nightingale was battling valiantly to improve conditions and save lives of wounded and dying soldiers. Dysentery, erysipelas, fever and gangrene were rife. She first arrived on November 5, 1854 with 38 nurses recruited in England. On the prompting of the Secretary at War, the doctors refused her help and only allowed her nurses to undertake menial duties. But the flood of wounded and sick forced officialdom's hand, and Florence Nightingale's influence grew accordingly. She had a fund of 30,000 Pounds to manage, and out of this purchased some of the necessities needed at the Barrack Hospital. She also worked with incredible energy and devotion, often going without sleep, superintending the multiple tasks that confronted her cleansing the wards, ensuring that fresh bed linen was available, tending the dying and arranging the preparation of special nutritious diets. Her success is beyond doubt. On her arrival at Scutari the death rate was 44%, six months later it had plummeted to 2.2%. She was rewarded with the adulation of the Victorian public. She died in 1910, still held in the highest regard.

Yes, women were in the camps at the Crimea in other than nursing roles.

In February 1855, the huge volume of public criticism and complaint toppled the Aberdeen government and Lord Palmerston became Prime Minister with Lord Panmure becoming Secretary at War. This resulted in some improvement in the organization and administration of the British Army, and as spring approached the chaos was slowly cleared. By March 1855, the morale was largely restored and the army stirred itself from its lethargy and despair, ready once again, to attack Sevastopol.

In spite of reinforcements, the allied forces faced a formidable obstacle. In truth, this was no siege. Since both avenues to the north and east were wide open, Russian troops could march in and out at will and supplies could be brought in at any time to sustain the garrison. The Allies did not have the forces for a direct assault; they had to reduce Sevastopol by artillery.

The allies made little headway in the first half of 1855 in spite of the death of Tsar Nicholas 1st. Indecision and arguments between the French and British command affected morale as did the soldiers' continuing battles with cholera and diarrhea. It was in this environment that Sergeant Wighton made his appearance. Soon afterwards, the battle was won. Co-incidence? We think not.

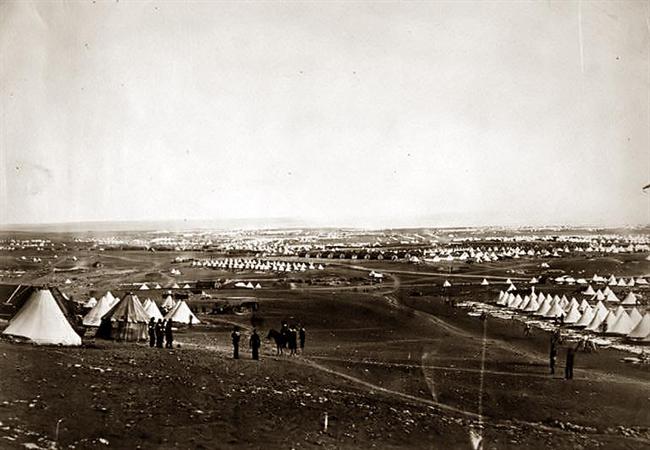

Camps on the Sevastopol plateau.

The final stages in the siege of Sevastopol began in August with huge artillery barrages. After the middle of August, the assault became almost incessant, cannon balls dropping like an unceasing storm of hail in forts and streets. On the 5th of September began a terrific bombardment, continuing day and night for three days, and sweeping down more than 5,000 Russians on the ramparts. Finally, on September 8th, the infantry followed up on the artillery barrage with direct assaults on the remaining Russian fortifications. The French assault was successful and Sevastopol became untenable. The Russians blew up their remaining forts, sunk their ships of war, and marched out of the town under cover of night. The next day, the Allied army marched into the ruins after eleven months of siege.

However, peace had not yet been declared, nor would it be for months yet. The allied armies remained, facing bitter cold of the winter. There was snow much of the time, never enough blankets, difficulty in thawing water, and men still dying from inadequate and very basic food rations. At last, on May 30th, 1856 peace was declared in the Crimea. Sergeant Wighton and the 72nd left in July, 1856.

Sources

Various web sites, including:

Charles Usherwood's Service Journal: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/crimea/usher/sebast1.html

The Crimean War http://www.batteryb.com/Crimean_War/crimea_part3.html

Old Pictures: http://www.old-picture.com/: Select picture collections/Crimean War