Tolbooth at Sanquhar, Dumfries & Galloway.

Cannongate Tolbooth, Edinburgh

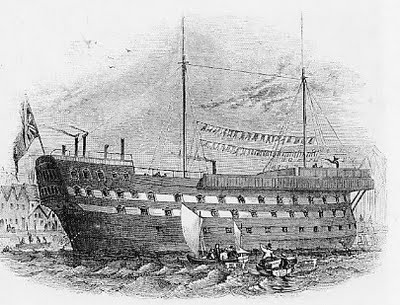

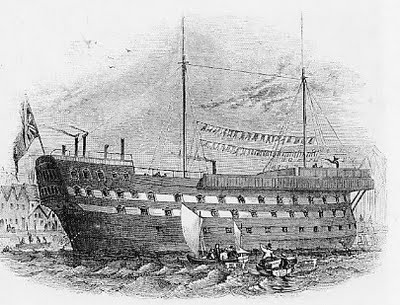

A prison hulk.

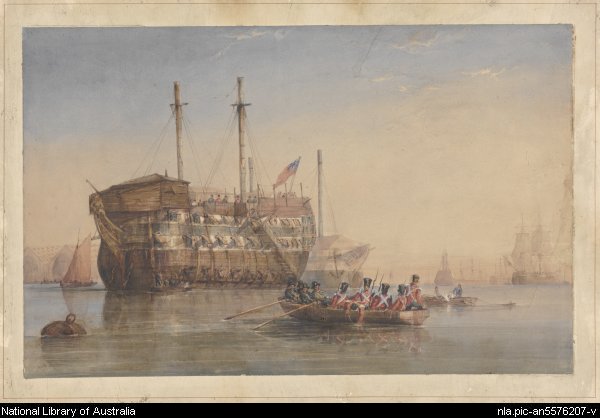

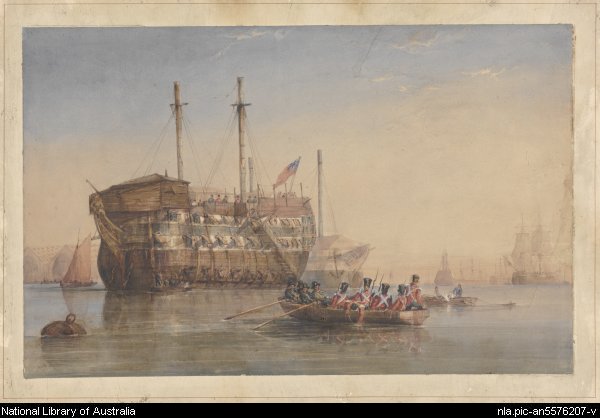

Arriving at a prison hulk

| Crime and Punishment in Scotland |

|

|

| Tolbooth at Sanquhar, Dumfries & Galloway. |

Cannongate Tolbooth, Edinburgh |

|

|

| A prison hulk. |

Arriving at a prison hulk |

|

The 17th Century In the seventeenth century, a complex and overlapping system of royal, ecclesiastical and private courts provided justice that varied from location to location. Every location had, in addition to its access to the higher courts (e.g., the Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh), a barony court with its own officers and a kirk session with its elders chosen from the community. The new office of Commissioner of the Peace was introduced in 1609. By 1663, there were 733 commissioners throughout Scotland. Disputes were commonly resolved by arbitration or taken immediately to court. Those who committed crimes were quickly identified and caught, and punishment was immediate and effective. Standards of proof and methods of determining fact and responsibility were very different from our current practice. Those subjected to the criminal courts, especially for serious crimes carrying capital punishment, were at the mercy of the courts which seem on the surface to have little interest in mitigating circumstances or motive. However, the courts did try to uncover the truth and a high proportion of prosecutions were dismissed. Confession was important – the reconciliation of the accused with God, the community and either the victims or their families being a necessary preparation for the execution of justice. Torture was not routinely employed in criminal cases, except for witchcraft. (The boot and the thumbscrews were used in political cases.) The idea that a corpse would bleed if touched by its killer was widely believed. Punishments were meted out rapidly and, to modern eyes, sometimes barbarously. They might include various forms of execution including beheading, hanging, burning, drowning with gradations of mutilations often preceding death. Capital punishment was applicable to traitors, witches, homosexuals, murderers, thieves, arsonists, forgers, rapists, and persistent adulterers. Imprisonment was rare, other than for debtors. Jails, or tolbooths, were chiefly used to hold prisoners awaiting trial, or after trial, until such time as they could be disposed of. For common people, if found guilty, this usually meant either execution, or banishment, or mutilation, or the payment of compensation. However, most penalties involved fines. The higher the victim's social standing, the higher the price. The compensation was awarded to the victim, if still alive, or to the kin if not. (The tolbooth was originally a booth at a fair where fines were collected, but which gradually transformed into a building were courts were held and prisoners kept before sentence.) The use of transportation to distant colonies was introduced in 1679 to get rid of (among others) political prisoners and prostitutes. But after both the 1715 and 1745 rebellions in Scotland, there were not enough prisons to hold political prisoners. Transportation came to be used to deal with prisoners, political and otherwise, but with the loss of the American colonies in 1775, there was nowhere to send prisoners to. The dilapidated hulks that used to be the transport ships were used as floating prisons because they were secure, and it was an expedient, but not an appropriate long-term solution. Court records indicate a low level of criminal activity in the 17th century, mostly petty pilfering and bickering between neighbours. However, the government was also concerned about maintaining social order. Vagrancy represented a form of subsistence migration, creating fear among the landowners in times of high unemployment or food shortages. Strict measures were instituted to regulate movement. Kirk sessions were required to issue certificates to those with legitimate reasons for being on the move and magistrates could resort to quite savage punishments like scourging and branding for those who flouted the law persistently. Maintaining social order was also behind the edict imposing the death penalty on sane children over the age of sixteen who cursed their father or mother. Witchcraft represented a threat to the spiritual order of the community. The majority of victims were women from the lower ranks in society. Prosecutions declined from the mid-1650s on as the elite and the judiciary became more skeptical of the accusations. Kirk sessions addressed themselves less with violence and property, and more with offenses thought to fall short of the ways of God. These included crimes of fornication, adultery, blasphemy, Sabbath-breaking, slanderous language, drunkenness, horrid swearing, and witchcraft. The 18th Century |

|

|

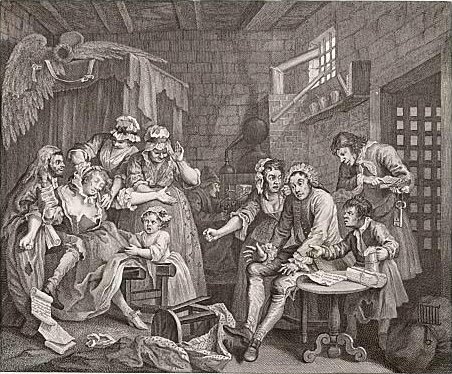

| Debtor's prison life. |

Debtor's prison, Southampton |

|

Gradually tolbooths, or prisons, began to be used as a form of punishment rather than as a temporary storage facility. Early prison reformers give us a glimpse into crime and punishment in the 18th century. For example, Samuel Romilly managed to get Parliament to abolish the death penalty for stealing more than a shilling, or five shillings worth of goods. John Howard urged improvements in Great Britain’s prisons through his role as Sheriff of Bedford. For example:

Prison time could be given to the following types of criminals: beggars; prostitutes who had already been banished from town for theft or other crimes; boys under fourteen convicted for stealing or house-breaking. As noted earlier, prisons were also used for debtors. Creditors had the power to arrest and imprison a debtor. After the debtor had been imprisoned for a month, the debtor could begin a process of cessio bonorum in the Court of Session. If the debtor could prove that he had fallen into debt through innocent misfortune, he could obtain the benefit of the Cessio. He had to grant all of his heritable and movable possessions to his creditors and he was then released from prison. In some cases, the court refused the benefit of Cessio to persons who had become insolvent through their own extravagance. The 19th Century Victorians were worried about the rising crime rate: offences went up from about 5,000 per year at the beginning of the century to about 20,000 per year in 1840. They were firm believers in punishment for criminals, but faced a problem: what should the punishment be? There were prisons, but they were mostly small, old and badly-run. Common punishments included transportation - sending the offender to America, Australia or Van Diemens Land (Tasmania), or execution - hundreds of offences carried the death penalty. By the 1830s people were having doubts about both these punishments. The answer was prison: lots of new prisons were built and old ones extended. The Victorians also had clear ideas about what these prisons should be like. They should be unpleasant places, so as to deter people from committing crimes. Once inside, prisoners had to be made to face up to their own faults, by keeping them in silence and making them do hard, boring work. Walking a tread wheel or picking oakum (separating strands of rope) were the most common forms of hard labour. We can get a glimpse of the nature of crime and punishment in the 19th century from this account about the situation in Dundee. Dundee in the 19th century was a rapidly growing manufacturing town and shipping port, attracting large numbers of people from across Britain in search of work in the jute industry. With an increase in population and wealth, crime rates began to soar, reaching epidemic proportions in 1820-40, with housebreakings, thefts, assaults and robberies with violence occurring frequently. (John Wighton the shoemaker moved to Dundee with his family around 1825.) The well-to-do citizens of Dundee carried pistols as they traversed the dimly-lit streets at night due to attacks by disguised and masked 'ruffians' demanding their purses or their lives. During this epidemic of lawlessness, the jail became inadequate for the numbers of prisoners detained within, and after a public meeting, plans were made for the building of a new jail. Up until 1837 when the new jail was built, the upper portion of the Town House had been used as a jail. The first official police force - the Police Commissioners, were appointed in 1824, with responsibility for lighting, paving and cleansing the town, and a concerted effort to provide gas lighting and pathways began. Prior to this, the Town Council and Magistrates would appoint Town Officers, who would patrol the streets, fetter the prisoners and guard the jails. As the 19th century progressed, the powers granted to Police Commissioners gradually increased, allowing them to undertake major town refurbishments in the 1870's. The granting of the Police and Improvement Bill Cleansing Act in 1871 saw the destruction of many of the seedier, overcrowded slum areas of Dundee, which had been seen as the sources of many criminal activities. As the town quickly grew and changed, so too did the types of crimes committed. Rioting was common in the earlier part of the century, often over the price and availability of food. According to records of the Circuit Court from the 1830's, thieves could receive at least 7 years transportation to Australia, while a bigamist could be sent to jail for 12 months. A large number of people in the jail were imprisoned for the non-payment of debts and separate cells were kept for these prisoners. In the 1870's, the problem with drunkenness had become problematic, and one policeman would bring in between 60 and 70 drunk men and women on a Saturday night. In the late 1870's, the crime of shebeening (selling alcohol without a licence) was one crime committed by more women than men, and in 1877, fines imposed on persons selling liquor without a licence raised almost £300 in revenue for the police. Temperance reform was a wide-spread and influential movement throughout the 19th century. Breaches of the peace and assault were also common crimes in these years. The 19th century justice system consisted of two courts, the Sheriff Court and the High Court (based in Edinburgh). Both of these courts travelled on a circuit to different regional locations where cases would be tried. The most common crimes to be tried in the Sheriff Court were theft and assault, and more difficult cases were referred to the High Court - the supreme criminal court of Scotland. In addition to being sent to Dundee jail or being transported to Australia, punishments included being sent to one of a number of other correctional institutions. Not only criminals, but people (especially children) at risk of becoming involved in criminal activities, could be sent to industrial schools. It was hoped that the kind of practical education provided in these schools would prevent them from slipping into a life of crime. Jails in the 19th Century |

|

|

| Prisoners on a tread wheel |

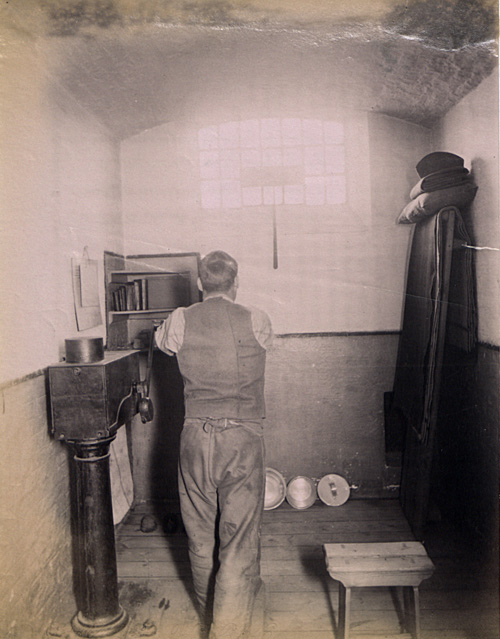

A prisoner turning a crank in his cell |

|

|

| Industrial School cooking class, Edinburgh, circa 1920. |

Industrial School carpentry class, Edinburgh, circa 1920 |

|

Prisons at this time were often in old buildings, such as castles, etc. They tended to be damp, unhealthy, unsanitary, and over-crowded. All kinds of prisoners were frequently mixed in together, - men, women, children, the insane, serious criminals, petty criminals, people awaiting trial, and debtors. Each prison was run by the gaoler in his own way. He made up the rules. If you could pay, you could buy extra privileges, such as private rooms, better food, more visitors, keeping pets, letters going in and out, books to read, etc. If you could not, the basic fare was grim. You even had to pay the gaoler to be let out when your sentence was finished. Law and order was a major issue in Victorian Britain. Victorians were worried about the huge new cities that had grown up following the Industrial Revolution: how were the masses to be kept under control? They were worried about rising crime. They could see that transporting convicts to Australia was not the answer and by the 1830s Australia was complaining that they did not want to be the dumping-ground for Britain's criminals. The answer was to reform the police and to build more prisons: 90 prisons were built or added to between 1842 and 1877. It was a massive building programme, costing millions of pounds. Many Victorian prisons are still in use today. People wanted to reform prison for different reasons. Christian reformers felt that prisoners were God's creatures and deserved to be treated decently. Rational reformers believed that the purpose of prison was to punish and reform, not to kill prisoners with disease or teach them how to be better criminals. There was more to Victorian plans than just bigger and better buildings. In the 1840s a system of rules called "The Separate System" was tried. This was based on the belief that convicted criminals had to face up to themselves. Accordingly, they were kept on their own in their cells most of the time. When they were let out, to go to chapel or for exercise, they sat in special seats or wore special masks so that they couldn't even see, let alone talk to, another prisoner. Not surprisingly, many went mad under this system. By the 1860s opinion had changed. It was now believed that many criminals were habitual criminals and nothing would change them. They just had to be scared enough by prison never to offend again. The purpose of the silent system was to break convicts' wills by being kept in total silence and by long, pointless hard labour. The Silent System is associated with the 1865 Prisons Act and the Assistant Director of Prisons, Sir Edmund du Cane, who promised the public that prisoners would get Hard Fare, Hard Board and Hard Labour. Hard fare was a deliberately monotonous diet with exactly the same food on the same day each week; and hard board was wooden board beds which replaced the hammocks that prisoners had slept in before. Hard labour was meaningless work such as the tread wheel shown above left. Designed in some cases to handle as many as 40 convicts, the device was composed of wooden steps built around a cylindrical iron frame. As the device began to rotate, each prisoner was forced to continue stepping along the series of planks. The power generated by the tread wheel was commonly used to grind corn and pump water. Prisoners walked on the tread wheel for eight hours, 10 minutes on and 5 minutes off. Hard labour could also be assigned to a prisoner in his cell (above right). The prisoner has to turn a crank in his cell a set number of times to earn his food. Unlike the treadmill, which provided some useful power, the crank simply turned paddles in a box of sand. Another form of labour was to require prisoners to pass cannon balls one to another down a long line. The point was to make the work hard and deliberately degrading in order to break the prisoner's will and self-respect. There were two types of jails in Scotland; the central jails such as those at Edinburgh, Glasgow, Perth and Aberdeen and the borough jails. The conditions were particularly bad in the borough jails where there was much overcrowding, often no privies, airing-grounds or chapels. The cells were usually filthy and the jailers did not live on the premises. Prisoners committed to jail for petty offences were often left in solitary confinement and lunatics were sometimes sent to borough jails. In Scotland, criminal law was graded according to the severity of the offence, from police courts, which without a jury could give sentences of up to sixty days, progressing to trials before the sheriff who could imprison for 3 to 18 months. More serious crimes were dealt with by the circuit court who could sentence offenders to transportation. A point of discussion was the experiment with the ticket of leave (parole) system. Many thought that the system was allowing some of the worst offenders back on to the streets. One man who had been sentenced to 10 years' transportation for robbery was caught committing the same offence at the same place a year later and was sentenced to 15 years. Within two years he was caught again and this time sentenced to transportation for life. Scotland had large areas with no police force, so it was very difficult to supervise these Tickets of Leave men. Fully one-quarter of them were reconvicted. After leaving custody, most of them found it difficult to find work and soon returned to their old associates. In 1878/79, female convicts in Scotland were confined in the general prison at Perth. There were no refuges in Scotland so the prisoners spent the whole period of their imprisonment at Perth. In the late 19th century, although penal servitude acted as a sufficient deterrent, it was claimed that it failed to reform offenders and it produced a detrimental effect through the indiscriminate association of all classes of convicts on the public works. Recommendations included:

Reformatories: Under the Scottish reform systems, the Industrial Feeding Schools of Aberdeen by 1851 had grown into four schools and a child's asylum. The schools were encouraged by the implementation of a new local Police Act in 1845; on the same day in October a school for juveniles was opened. The police were ordered to round up all begging boys and girls in Aberdeen and carry them to the school. That day 75 were captured. The children on their first day were forcibly washed and then during the day given three substantial meals. In the evening they were told attendance was voluntary but that begging was now illegal and would be punished by imprisonment. On the next day all returned except three. All the schools were supported by voluntary contribution and employed paid staff. The idea being to get children into the school at as young an age as possible before they had formed bad characters. Most of those taken in were under 11. The routine of the schools was a mixture of teaching, industrial training and feeding. Sources Various web sites, including: Crime and punishment: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/candp/punishment/g09/default.htm Crime and punishment in the 19th century: http://www.dundeecity.gov.uk/lamb/crime.htm Prison and punishment in late 18th century Scotland: http://sites.scran.ac.uk/ada/documents/castle_style/bridewell/crime_and_punishment_in_eighteenth_century_scotland.htm Reformatories and Industrial Schools in Scotland: http://www.workhouses.org.uk/index.html?IS/Scotland.shtml Scotland in the 19th Century: http://gdl.cdlr.strath.ac.uk/haynin/haynin0204.htm Why were Victorian prisons so tough? http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/lessons/lesson24.htm |