Cholera was one of the most feared epidemic diseases of the nineteenth century. Previously unknown in the western hemisphere before 1830, four high mortality epidemics hit Scotland in the middle of the 19th century. Today we know that cholera is an infectious gastroenteritis bacterial disease transmitted from human to human by ingesting contaminated water or food. The bacteria produces a toxin that acts on the lining of the small intestines to induce massive diarrhea. In its most severe forms in the 19th century, cholera was one of the most rapidly fatal diseases known and infected patients could die within three hours if treatment was not provided. More commonly, death occurred after 18 hours to several days without therapy. Cholera spread quickly through germ-infected bedding or personal touch contact with infected victims.

Cholera was first reported in Asia around 1830 and spread rapidly through Europe and to the British Isles at first through the cities exposed to international trade (like Glasgow and Dundee). Major cholera outbreaks hit Great Britain in 1831/32, 1848/49, 1853, and 1866. The 1832 epidemic caused 22,000 deaths in England and 10,000 deaths in Scotland. Glasgow alone suffered 3,000 deaths. Dundee’s 1832 epidemic lasted 30 weeks with over 800 people infected and over 500 succumbing to the disease. In the 1848 epidemic, England and Scotland had over 60,000 deaths, including about 14,000 in London. Cholera created panic because 50% of those who contracted the disease in 1832 died. Another reason was the fact that it struck at all social classes. The infectious disease spread easily and it knew no class boundaries - everyone was at risk and no-one really knew how the disease was spread. It was only after the second epidemic that progress was made in properly identifying the root causes. [Aside: During the first half of the century, the death rate was lower in the rural parishes than in the principal towns. This was largely due to the fact that people living in the country were spread out over a large area, which meant that in times of epidemics they had a natural system of quarantine. The generally healthier environment in the countryside also helped build up resistance to disease. This trend was reversed at the end of the 19th century when returning migrant workers from the Lowland cities brought tuberculosis with them and the damp condition of the housing saw it spread like wildfire through the Highlands.](Right, an image of a young cholera victim in 1831.)

Today we know that, as Scottish industry had flourished, more people had been drawn towards urban areas. In mid-century, city populations also increased as a result of Irish emigration resulting from the failure of the potato crops. Overcrowding became a serious problem. In Dundee, for example, the jute boom of the 1850s had led to a sudden, huge increase in the population of the city, and the housing stock simply couldn't keep apace. The result was overcrowding and slum areas, which were to become the scourge of Scotland's cities for many years. Conditions in the slums were appalling - at one point there were only five water closets in the whole of Dundee, three of which were in hotels. There were no sewers until the 1870s. Piped water was introduced in 1845 but was available only to those who could afford it. Only at the end of the century did piped water became commonplace. (Left, from the Housing and Health website, an 1863 image of an attic occupied by a family of 10.)

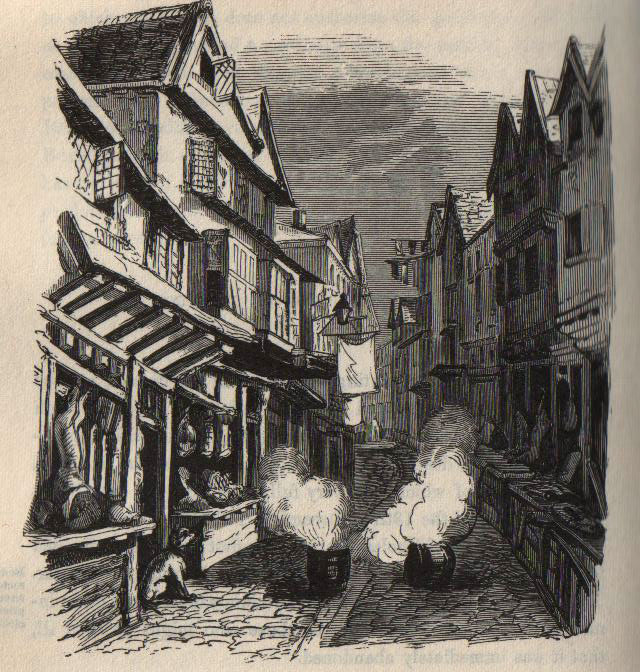

In Glasgow the problem was just as acute. In the poorer areas, an estimated 20,000 people were crammed into dilapidated housing where sanitation was virtually non-existent. Twelve to sixteen people sleeping in a room was not uncommon in the poorer parts of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Overcrowding was only part of the problem - dirt bred disease and Scotland’s cities had plenty of disease-generating environments. For example, Dundee in the 19th century was smelly and crowded, with noisy markets and narrow cobbled streets traversed by horses and carts and littered with deposits of horse dung. Street-side butchers and fish vendors would often toss innards and unwanted flesh into street gutters, and householders threw refuse from tenement windows into the streets below. In the early 1800s, toilets were outdoors and shared by many families living in the same tenement block, and few public washing facilities were available for bathing. Dung heaps were often situated too close to public wells and triggered complaints from citizens about their drinking water being contaminated with feces. Many families were poor and children were known to rummage for 'rags and bone' in people's 'dung heaps' under their houses. Not surprisingly, disease was rife. (Right, an 1852 Punch cartoon with a refuse heap front, left.)

However, finding a cure for killer diseases proved difficult due to conflicting opinions among doctors as to the causes of disease. The Miasmatic school of thought was convinced that the cause of disease was due to toxic odours in the atmosphere. These were the result of dirt and poor sanitation. Their solution was to clean up the streets and provide an efficient means of disposing of human waste. For example, officials in Exeter, England ordered fumigations, the use of chloride of lime, whitewashing, general cleansing, and the destruction of the clothes of those who had died. The bodies of those who died of cholera were directed to be enveloped in cotton or linen, saturated with pitch, or coal-tar. This proved, however, so serious an annoyance to the other inmates of the house, especially to those who might be then ill, that it was immediately abandoned. Fumigation of different kinds were freely used, for example, officials ordered the lighting of fires with tar in the most confined parts of the city, in order to purify the air. Vinegar and chloride of lime were distributed to families for burning as well. The other school of thought on the origin of cholera were known as the contagionists. They believed that disease was spread by touch and originated in contaminated water supplies. This latter view dominated the thinking of medical men in Scotland. They did not oppose sanitary reform but saw the provision of pure drinking water as a first priority.

It took several decades after the 1831/32 epidemic before progress was made. In Glasgow, for example, the city’s doctors had demonstrated a link between dirt and disease in 1842, but it wasn't until the cholera epidemics of 1848 and 1853 that this became the focus of the medical community. In 1855 the national government made the registration of births, deaths and marriages compulsory. Among the information gathered was the cause of death. James Burns Russell, one of Glasgow's pioneering medical health officers, realised that the filthy environment was promoting the spread of disease and he used the new registration information to help persuade Glasgow's City Fathers and reluctant rate-payers to fund an ambitious engineering scheme to bring a clean water supply into the city. This scheme, combined with Glasgow's new sewage system, of which nearly 50 miles was laid between 1850 and 1875, began to ease the health and sanitation problem in Glasgow; however, other smaller Scottish towns were more reluctant to pay for such huge enterprises and were characterised by an overpowering stench for much of the 19th century. By necessity, the cities led the way in public health issues. Sanitary Departments and Medical Officers were appointed who forcibly removed middens (dunghills) from under people's noses. (Right, there was no supply of water in the houses, so it had to be collected from the street.)

Cholera wasn't the only high risk disease that Scots faced. Typhoid fever, diphtheria, scarlet fever, influenza, and tuberculosis also killed thousands.

Sources

Various websites, including:

A Chronology of State Medicine, Public Health, Welfare and Related Services in Britain 1066-1999: http://www.fphm.org.uk/resources/AtoZ/r_chronology_of_state_medicine.pdf

Shapter, Thomas (1832). The History of the Cholera in Exeter as excerpted at http://www2.plymouth.ac.uk/millbrook/cholera/shaptfum.htm

A History of the Scottish People: Health in Scotland 1840-1940: http://www.scran.ac.uk/scotland/pdf/SP2_3Health.pdf

Cholera in the 19th Century: http://sites.scran.ac.uk/lamb/cholera-pages/L308(31).htm

Urban growth in Victorian Scotland: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/victorian/features_victorian_urban.shtml

Wilkipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cholera