Picture fuzziness is due to the poor technology of the CIA's satellite imaging services in the 1860s.

Until the mid-19th century, the British army allowed a handful of soldiers' wives to accompany the troops to duty stations and even to war. Army wives were present in almost every theatre of war in which Britain was engaged, including the American War of Independence, the wars with Napoleon, and the Crimean War. (After the Crimean War ended, in 1856, wives were no longer allowed to go on battle campaigns.)

Women were considered part of the regiment. They were restricted by its rules (e.g., whether they could travel with the regiment, whether they could accompany their husband into battle (for those who were traveling with the regiment), whether they could live in married quarters, and how much rations they received. When a married solder died, his widow and their children, as well as orphans, were provided with passage back to the British Isles. And, until they were able to make their way home, women who lost their husbands were cared for by the respective regiments.

Since a soldier's marital status could have an effect on his ability to serve, and since his wife could become a part of the regiment if he died, it follows that the soldier's commanders would have some say over whether or not he should be allowed to marry. Here are five articles from British military orders. (Note that these regulated army life in the 18th century so they may not be entirely appropriate for John's regiment.)

- Article I: Officers being guardians to the men in their respective companies, should use every means that prudence can suggest, to prevent the distress and ruin which so often attends their contracting marriages with women, in every respect unfit for them.

- Article II: The principal method by which they can hope to guard against so great an evil, is to fix a standing order, for no non-commissioned-officer, drummer, or private man to marry without the consent of the officer commanding the company he belongs to, which he should not grant on any account, until he has first had a strict enquiry made into the morals of the woman, for whom the soldier proposes, and whether she is sufficiently known to be industrious, and able to earn her bread: if these circumstances appear favourable, it will be right to give him leave, as honest, laborious women are rather useful in a company.

- Article III: On the contrary, if he finds the woman's character infamous, and that she is notorious, for never having been accustomed to honest industry, he should represent these matters in the plainest terms, and recommend it strongly to him, not to think of persevering in a measure: if after such an admonition he is imprudent enough to marry, in justice he deserves a punishment for his folly and disobedience.

- Article IV: It will also be another expedient towards preventing improper marriages, if, upon the arrival of a company in a town, application was made to the Minister of the Parish, to request he would not publish any soldier's intended marriage in his church, without first receiving a certificate from the officer commanding the company of its being agreeable to him.

- Article V: A soldier marrying with proper consent should be indulged, as far as can be in the power of officers to extend their favour, whilst his behaviour and that of his wife deserves it; but he who, contrary to all advice and order, will engage in a dishonourable connection, exclusive of any punishment he may receive for such contempt and insolence, should as much as possible be discouraged, by obliging him not only to mess, but lie in the quarters of the company he belongs to, at the same time that his wife, is prevented from partaking of any advantage either from his pay or quarters: this severity of course must soon expel her from the regiment, and be the certain means, of making other soldiers cautious how they attempt such acts of disobedience.

There were a limited number of married quarters in the barracks and assignments were made on the basis of rank only. Wives who married without leave, or those who had no access to the married quarters, lived in lodgings or shanties around the garrison town.

Only a certain number of wives were allowed to accompany the army on its transports. That exact number is not clear. A British regiment, which typically had ten companies, was allowed six women to each company for embarkation. This works out to about one woman for every ten men. However, there was no single, hard and fast proportion of women allowed to accompany a regiment on foreign service. More importantly, it is not necessarily true that the orders were followed. Also, the quota applied only to the use of military transportation. It did not address the number of wives allowed to be with regiments after their arrival. (This last point is important since Catherine did not travel to India with John - she was giving birth to John Murray Wighton in Dundee. However, we know that she joined John in India at some point because his third child Harry is buried there.) An entry on the web reported that, in 1898, a wife was allowed to join her husband in India after he had been there six months. The same law may have been in effect at the time of the Indian Mutiny.)

Those women who were unlucky faced a long wait before they saw or heard from their husbands again. Some women, hearing nothing for years, assumed that they were widows and married again, only for their soldier husbands to return from the wars, rendering them unwitting bigamists. Apart from anxiety and uncertainty, hardships shared by modern spouses, the soldiers' wives left behind prior to the 1850's often had to face homelessness and destitution. Only a small number were permitted to remain in the barracks; the rest had to depend on the charity of their families, or throw themselves at the mercy of the authorities.

Clearly, John Wighton would have received permission from his Commanding Officer in Fredericton to marry Catherine. It's also fairly certain that Catherine was allowed to accompany the regiment on its departure from Canada. The regiment may have had a 'below quota' number of wives with them seeing as how they hadn't been in England since 1844. Or, for the romantic at heart, we could speculate that the regiment's Commanding Officer gave John a promotion to Colour Sergeant prior to the wedding so that he could get married and receive favourable consideration for lodging for him and his wife. According to one web site that I read, staff (colour) sergeants were allowed to marry, but only 50% of lower sergeants were given permission.

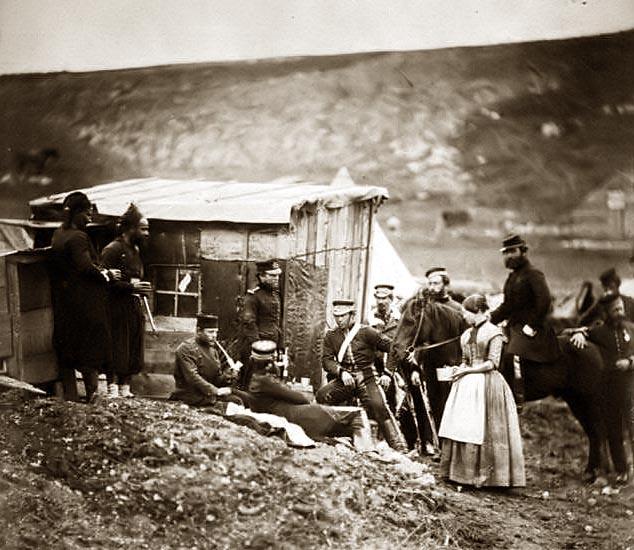

For those women who were allowed to accompany their husbands, their lives were not all sweetness and light. (Above, a British woman in the Crimea war campaign.) Wives were given half rations and their children a third or quarter ration. If they were in a battle zone, they had to share all the hardships and work to support themselves and their families. This frequently entailed laundry or seamstress work for soldiers; however, they might also be employed as a nurse to the regiment provided that their husband didn't take ill. If this happened, the wife had to be dismissed or her pay discontinued until her husband had recovered. (Note that this description may not have applied to wives of the 1850s.)

While the Army took care of sending widows and children back to Britain, after that they were on their own. Similarly, they were on their own if they were left behind in Britain while the husband was on assignment. In 1854 the Earl of Shaftesbury launched an Association, with Queen Victoria as patron, for the "Aid of Wives and Families Ordered to the East" (i.e., Crimea). The Caldwell reforms of the 1870s made soldiers liable for the first time for maintenance of his wife and family. Previously they had to seek Poor Law relief from the parish.

Sources

Wives and Children of the British Army: http://www.royalengineers.ca/femnkid.html