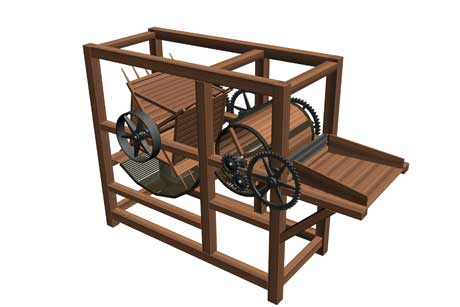

A thresher from the Industrial Revolution

From the Union in 1707 through to about 1745, Scotland experienced a state of extraordinary langour and debility. Her trade was inconsiderable, her agriculture in the most wretched state of neglect, and her manufacturing virtually nonexistent. Her people were oppressed, abject, and dispirited; and there seemed to be no hope of ever seeing a spirit of active industry excited in this nation. In reality, the Scotland of the time was a poor, backward country - even in comparison to the other underdeveloped countries of the time. (From Smout)

In terms of its farming practices, agriculture in Scotland was in an extremely backward state. The picture which emerges from many of the accounts, as from other sources, is one of a land largely undrained and unfertilized, often choked with weeds; of crop rotations and planting dates firmly fixed by tradition, with all attempts at innovation met with deep suspicion or downright antagonism; of cumbersome, antiquated implements and malnourished livestock. Not surprisingly therefore, times of scarcity, even of actual famine, were by no means infrequent. (From Stephen)

After 1750, change began to gradually occur as Scotland entered an intellectual Golden Age that became known as the Age of Reason. A scientific-founded inspiration promoted the optimistic belief that life and society could be planned, ordered, and improved if only men would use their intelligence. As the eighteenth century proceeded, a 50% rise in the birth rate and a shift of population to the industrial cities created a demand for food which traditional agriculture could not meet. The old style subsistence farming was no longer adequate to meet the needs of this population and it gave way to profit-based agriculture supplying the town dwellers. This shift was accompanied, and enabled, by the establishment of a network of turnpike roads which greatly increased the flow of goods - farming equipment, fertilizer from the cities to the farms and agricultural products from the farms to the cities.

Thus it was that intellectual promptings, commercial expectations, and improved transportation combined to encourage efforts to increase the productivity of the land. Over time, the organization of the land was replaced by enclosure, and long leases granted to encourage effort. Walls or hedges and tree plantations provided shelter from the elements as well as protection against straying animals. The soil was drained, cleared of peat and moss, and fed with lime; thus treated, more acres could be brought into cultivation, and those already in production could be enriched. Proper crop rotation patterns, summer fallowing, autumn plowing, winter-sown wheat, improved equipment, and other innovations were introduced, helping to ensure that land could remain more or less constantly in production. New crops were encouraged (e.g., flax, potatoes, turnips, grass seed for hay). The introduction of flax provided opportunities for estate workers to develop the skills necessary for spinning linen yarn which facilitated the revolution in linen production that was occurring at the same time .

Meanwhile, industrial improvements produced improved agricultural equipment. The new, lighter plow (Small's Plough) is shown above. Small introduced a pattern of curves to the mould board which could efficiently cut into the soil and simultaneously turn over the turf and expose fresh soil, creating the type of furrow we recognize today. The wrought iron sock and mould board were beaten to the most efficient shape by local blacksmiths according to Small's patterns but later implements were accurately manufactured in cast iron. Seeding machines, mechanical reapers, and mechanical threshers (see image at the top of the page) were also introduced and they greatly increased production.

The change in the life of the farmer was profound. Here's an excerpt from the 1791-99 Statistical Account of Scotland written by the Minister of the Meigle Parish.

"Since the year 1745, a fortunate epoch for Scotland in general, improvements have been carried on with great ardour and success. At the time, the state of the country was rude beyond conception. Gentlemen with enlightened and liberal minds formed plans of improvement, enclosed farms with proper fences, banished sheep from infield grounds, combated the prejudices of their tenants, furnished them with marl, distributed premiums and otherwise rewarded their exertions. The good effects of those measures soon appeared; and other proprietors imitated the examples. In a few years, improvements were diffused through the whole country. The tenant, as if awakened out of a profound sleep, looked around, beheld his fields clothed with the richest harvests, his herds fattening in luxuriant pastures, his family decked in gay attire, his table loaded with solid fare, and wondered at his former ignorance and stupidity."

Sources

Smout, T.C. (1998). A History of the Scottish People, Fontana Press.

Steven, Maisie C. Parish Life in Eighteenth-Century Scotland, Scottish Cultural Press.

Various web sites, including

Rural Life in the 18th Century (www.electricscotland.com/history/rural_lifendx.htm)

Scottishmist (www.scottishmist.com)

Statistical Accounts of Scotland (http://edina.ac.uk/stat-acc-scot/)